(Installation View, pp. 67–84)

On the evening of 23 June 1884, the first annual exhibition of work by members of the Amateur Photographic Association of Victoria opened in the hall of the Royal Society of Victoria (an appropriately regal building that still stands on the corner of La Trobe and Victoria Streets in Melbourne’s CBD). Ironically, given this may indeed represent ‘the first purely photographic exhibition held in Australia’, as a newspaper article retrospectively claimed in 1890, there appear to be no photographs documenting this exhibition.1 Newspaper reviews note that as well as ‘ordinary photographs’ there were ‘stereoscopic pictures, transparencies [‘views, and photographs of Collingwood identities shown in the optical lantern’], coloured photographs, daguerreotypes, talbotypes and specimens of crystoleum painting [photographic emulsion and painted colour on shaped glass]’2. The walls were ‘profusely studded with portraits’ and although the focus was squarely on Victorian faces and landscapes, the exhibition also included ‘some interesting photos of natives of Japan … having been executed by Japanese operators’.3 The amateur work was supplemented by well-known professionals such as Charles Nettleton and J. W. Lindt, as well as ‘photomechanical printing of all descriptions’ by the photographic educator Ludovico Hart (some of which had been shown previously at the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition).

The 1884 exhibition marked the first anniversary of the Amateur Photographic Association of Victoria, founded during a decade when Melbourne’s economy enjoyed boom conditions (the term ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ was coined in 1885 by a visiting journalist, and by 1889 the value of land in parts of Melbourne was as high as London). The Association was formed ‘for the purpose of exchanging photographs between one amateur and another, the formation of a standard photographic library and the cultivation of a closer acquaintance with amateur photographers for their mutual benefit’, and by the end of its first full year it had forty-three members.4 Echoing the development of annual salons across the world, the availability of cheap, mass-produced cameras and printing papers, along with the increase in leisure time for activities such as bicycling and boating, had given rise to legions of amateur photographers eager to show their work to peers and the public. At the well-attended opening of the first annual exhibition, Hart – who in 1887 went on to establish the photography course at the newly opened Working Men’s College, now RMIT University – gave a lecture ‘on the rise and progress of photography’.5

The second annual exhibition of the Association was held in late June 1885, in a congregational hall on Russell Street. As a review in The Argus newspaper pointed out, ‘the title is somewhat misleading, for the works of amateurs compose a portion only of the display, to which professional photographers and dealers in photographic materials have largely contributed’.6 The professional work included Lindt’s portraits and interiors as well as photogravures from art dealers and publishers Goupil and Co. in Paris and numerous photographs of the architectural antiquities of Rome. Photographic retailers helpfully laid out all the new kit that keen amateurs would need – tripods, cameras, lenses, dry plates, stereoscopes and ‘other appurtenances of the black art’. The Argus complained of the poor lighting in the venue:

Unfortunately, the artificial light projected on the walls from a couple of circular gas-lights in the roof is far too feeble to admit of such a critical examination of the numerous photographs exhibited as would enable us to speak with anything like confidence of their positive or comparative merits. The best under such circumstances, is scarcely distinguishable from the worst. Now, a sun picture, being the creation of a powerful light, requires to be scrutinized by the light of day. Otherwise the delicacies of its detail, its tone, its gradations, its perspective, the strength of some portions of the picture and the softness of others, elude observation.7

A review in The Age similarly complained that the room was ‘so badly lighted that it is difficult to distinguish good work from bad’.8 The reviewer concluded that:

On the whole, the art element is not a prominent feature in the exhibition, at any rate as far as the amateur exhibits are concerned and the visitor who examines these productions only might be disposed to agree with the old mot of Punch that photography was joe to graphic art. He has only to look around, however, to the beautiful photogravures by Goupil and the masterly portraits by Lindt and other of our local artists, which have been lent for the adornment of the room, to see how imperfectly the possibilities of the art were guessed at but a few years ago.9

It was clear that photography was separating into distinct fields as it increased its reach, and by 1886 the Amateur Photographic Association of Victoria numbered over 100 members and the annual exhibition was confined to amateurs.

The 1888 exhibition, held at the Athenaeum in December, included two spectacles which starkly demonstrated the increasing capacity, scale and speed of the medium: ‘hundreds of pictures of the most beautiful and characteristic scenery of Australasia’ were projected on a ‘20 foot disc brilliantly illuminated by the oxyhydrogen limelight’ (the largest screen ever used in Melbourne). Secondly, a ‘photographic novelty’: ‘the hall and its occupants are photographed each night instantaneously [by the new magnesium flashlight process] and a transparency of it shown on the screen on the following evening’.10 By 1895, despite a dramatic downturn in the Melbourne economy, the Amateur Photographic Association of Victoria was respected enough to warrant a full room with ‘several hundred’ photographs at a major art exhibition held in the galleries of the Royal Exhibition Building in connection with the nearby aquarium. A review in Table Talk glossed over the 200 paintings by Victorian artists to focus on the ‘the present state of perfection to which photographers have brought their art’. An installation view of the room illustrates that most of the photographers presented their work in what were described as ‘a frame of views’, collections of smaller photographs in a large frame. Although there were many examples of new processes and technical prowess, a few works were also singled out as being ‘poetical’. For instance, the reviewer noted that J. C. Kaufmann (not John Kauffmann, the later pictorialist) ‘has worked up a poetic idea in his solitude on the rocks’. The review also notes that the art exhibition included the largest ‘Autotype’ (carbon print) ever brought to the colonies. It was an enlargement made by the Autotype Company from a negative of a lion in zoo exposed by the popular British animal photographer Robert Gambier Bolton. Elaborately framed and grandly titled Majesty, the enlargement hung near another Autotype Company reproduction of Jean-François Millet’s painting The Gleaners, 1857, as well as other framed paintings. The image was displayed the following year at the Photographic Society of Great Britain Exhibition in London.

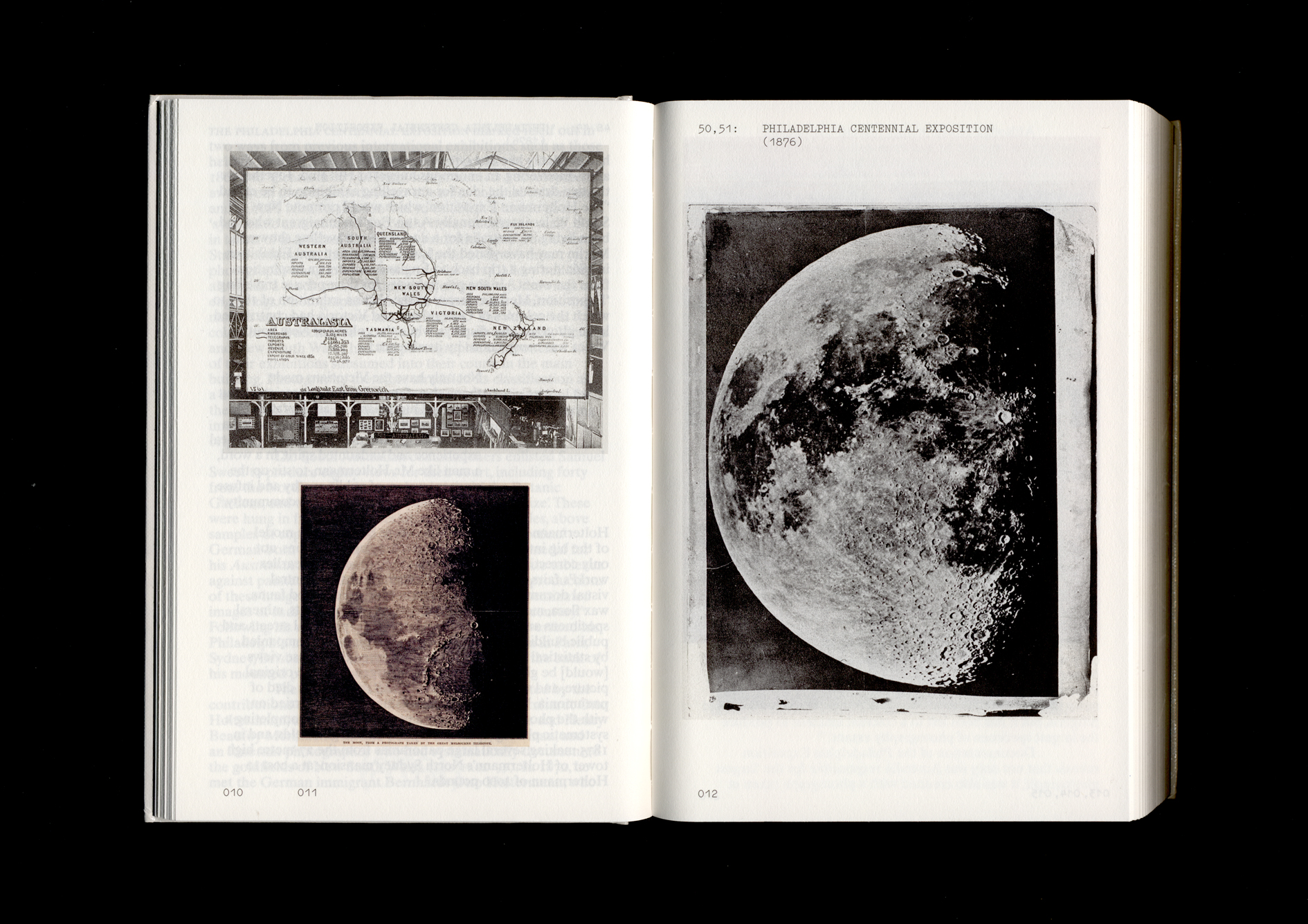

Over Easter in 1895, the Gordon College Photographic Association held an ‘intercolonial exhibition’ and ‘congress of Australian photographic societies’ in Geelong, even arranging ‘carriage by railway, free of charge’ for all the exhibits.11 At the congress, Ludovico Hart gave a ‘lecturette’ accompanied by ‘micro-photographic’ lantern slides, while G. F. Link showed stereoscopic pictures which ‘when viewed through coloured spectacles … presented pleasing and excellently effective pictures’.12 The astronomer Edward Sells from the Adelaide Observatory projected a ‘beautiful display’ of lantern slides picturing the sun, the moon and the stars to a ‘large appreciative gathering’.13 The Geelong exhibition, consisting of over two thousand items from amateur photographic societies around Australia, was such a success that when it closed the trustees of the Melbourne exhibition invited the photographs to be sent to Melbourne for exhibition at the Royal Exhibition Building.14

The South Australian Photographic Society, formed in 1885, arguably had the biggest influence on the development of Australian photography, after John Kauffmann joined upon his return to Adelaide from Europe in 1897. Having seen an exhibition at the Photographic Society in London that included the work of pioneering pictorialists such as Henry Peach Robinson and Alfred Horsely Hinton, and spent six months in the Vienna studio of a fashionable portrait photographer, Kauffmann imparted the ideals of a European impressionistic style of art photography. He showed prints by Hinton that he had brought back with him, which ultimately had a profound effect on his Adelaide contemporary Harold Cazneaux.15 The Society’s International Salons also included the work of Julia Margaret Cameron in 1902 and Henry Peach Robinson in 1903. In 1897, Kauffmann exhibited enlargements on pearl bromide paper in Sydney and Adelaide, and in a bold move, he submitted them directly to the Society of Artists in Sydney for inclusion in their annual exhibition. Although rejected for this exhibition, they were instead selected for exhibition at the Sydney showrooms of the prominent photographic supplier Baker and Rouse to some critical acclaim (‘Kauffmann is an artist as well as a photographer’).16 In 1899, Kauffmann won first prize in the landscape class at the Photographic Society of New South Wales’s Intercolonial Exhibition.17 By 1901 he was invited to judge his own society’s annual exhibition, along with his former art teacher H. P. Gill. The 1901 exhibition of the South Australian Photographic Society was considered ‘one of the finest’ by the reviewer for the South Australian Register, as ‘some of the works could be mistaken for works of art’. F. A. Joyner and Fred Radford, also of Adelaide, were also exhibiting by this time, showing different influences from Europe.

The Photographic Society of New South Wales was formed in Sydney in 1894, and from 1899, in an effort to raise standards, international competitors were invited to show alongside Australians at its annual exhibition. The Society’s International Salon of 1903 included gum-bichromate and gravure prints by the prominent pictorialists David Blount, from Britain, and Edward Steichen, from the United States. Their low toned subsuming of photographic detail under brushed on emulsion and hand applied ink caused robust debate amongst Sydney’s photographer, but these prints were singled out for special praise by the local aestheticist painter and critic Sydney Long.18

Pictorial photography, as the art historian Gael Newton suggests, ‘opened the way to a career as an artist or an identity as an aesthete for many who lacked facility in the fine arts or academic training in painting and drawing’.19 By the end of the nineteenth century, the annual salons held by the various Australian photographic societies had become a regular way for local photographers to view examples of the latest pictorial styles. Moreover, salons abroad were a way for Australian photographers to receive coveted international recognition. Kauffmann won numerous silver medals in London, and in 1911 the pre-eminent New Zealand-born, Sydney-based photographer Harold Cazneaux received extraordinary praise when his sun-splashed print The Razzle Dazzle was exhibited at the London Salon:

The Razzle Dazzle … is enormously daring, enormously successful. Stieglitz in his days of best production, possibly Frank Eugene, and just possibly Coburn … Not one of them would have treated it better; probably only Stieglitz would have handled it quite so well.20

Locally, Cazneaux’s prints had been standing out from the crowded frame-to-frame and wall-to-wall jumble of camera club exhibitions well before 1911. By 1907, as a new member of the Photographic Society of New South Wales, he was winning many of the competitions.

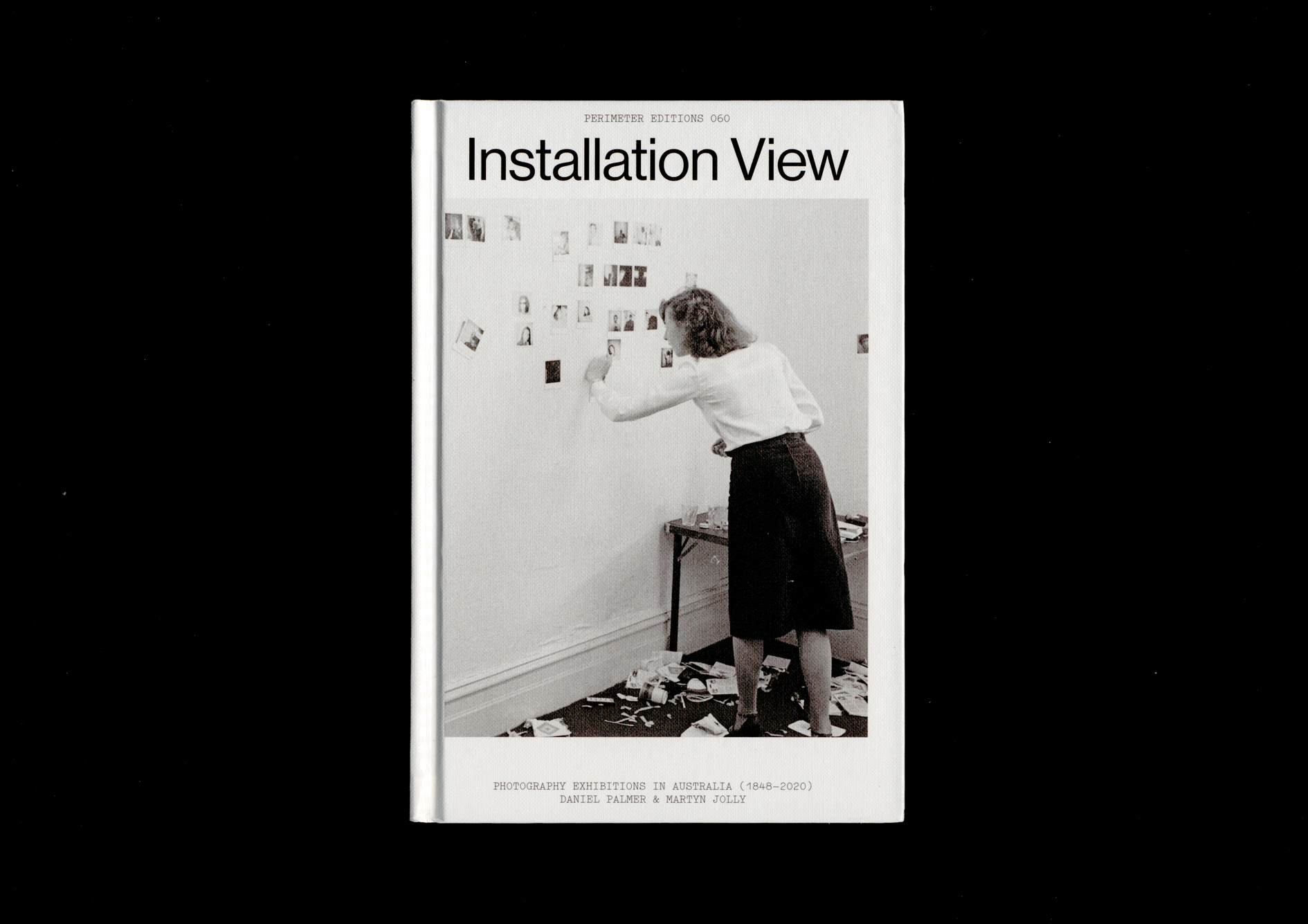

Cazneaux was ambitious and also an excellent self-promoter. In March 1909, he held an exhibition of seventy-six carbon and bromide prints in the tastefully decorated rooms of the Photographic Society of New South Wales in Hamilton Street, Sydney. The exhibition, which included landscapes, seascapes, ‘picturesque city corners’21 and portraits, was a critical success. As The Sydney Morning Herald declared:

Following the lead of some of the American and old-world photographers, he uses the camera merely as an aid to artistic achievement and while many of his pictures are provocative of the old controversy as to the real bounds of legitimate photography, the aesthetic effect he secures in undeniable. The collection includes many everyday city and harbour scenes, which have been invested with singular artistic charm by a broad impressionist treatment.22

Cazneaux’s 1909 exhibition was undoubtedly the first solo exhibition by any Australian photographer, which was soon followed by an exhibition of seventy-four of Kauffmann’s photographs in Melbourne in 1910 (hosted by the Photographic Association of Victoria after he had relocated to Melbourne). Kauffmann had been a key influence on Cazneaux and, as Newton suggests, ‘may have been the only photographer of his generation to survive largely on sales of his work in the manner of traditional artists’, but he ‘was not a natural leader or proselytiser of the new style’.23

The Australasian Photographic Review praised Cazneaux’s solo exhibition, noting one photograph in particular, which ‘shows what can be done even with an everyday subject that any energetic camerist can secure in his lunch hour, if he is gifted with the “seeing” eye’.24 The same review also pointed to excessive ‘brush work’ in some of the photographs, declaring ‘faking of the negative is perhaps permissible, but the resulting print should not require the addition of crayon or paint’.

Sydney’s pictorialists had been criticised for their lack of attention to mounting,25 but documentation of Cazneaux’s exhibition reveals his careful attention to mounting and framing. The prints were presented in light coloured mats, some were glazed, and all were taped around the edges to form a visual frame. As the Australasian Photographic Review observed:

Cazneaux has mounted his prints in passe-partout style and no photographer should miss seeing the show if only to learn what can be done with this, the simplest and most economical method of framing up prints for home decoration.26

The frames were hung in two relatively uncongested rows along the walls of the Society’s rooms, and each was numbered and priced. A vase of flowers on a table added a touch of elegance to the display. As Newton has observed, Cazneaux’s ‘One-Man Show’ – as its catalogue proudly stated in large letters – established his pre-eminence in the pictorialist sector of Sydney photography.27 Indeed, Cazneaux soon became a leader of the elite Sydney Camera Circle, formed in 1916. Most importantly, Cazneaux’s exhibition formalised the presentation of the photographer as an artist.

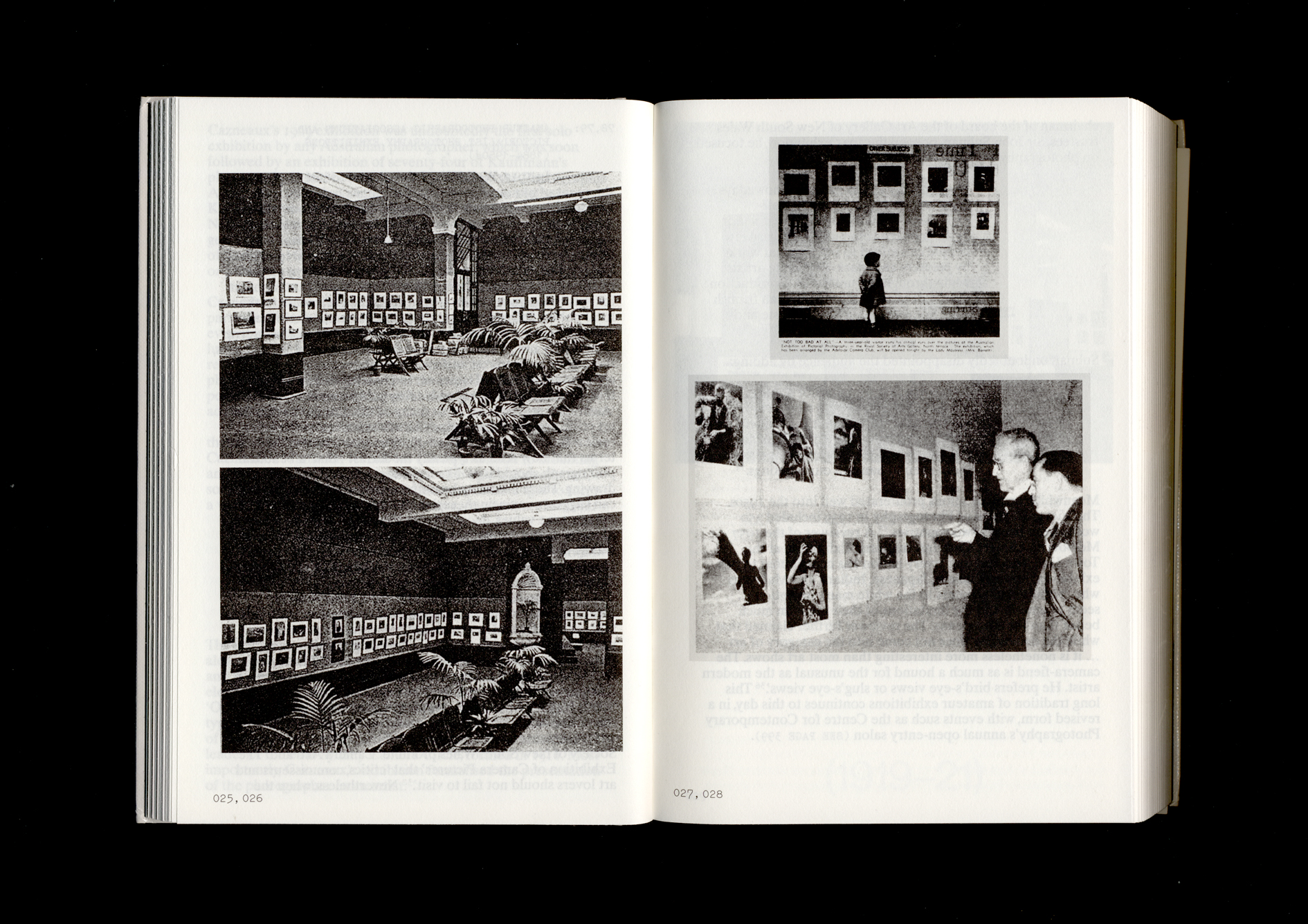

In 1917, World War I threatened to interrupt a shipment of mounted prints by Australians trying to enter the London-based Amateur Photography Colonial Competition. As a result, the Photographic Society of New South Wales organised their own exhibition of Australian Pictorial Photography in the Art Gallery of the Education Department, Sydney. The exhibition comprised no fewer than 279 pictures by fifty-four photographers and marked a significant moment for Australian pictorialists. They presented their work to the local public, fellow photographers, and Australian critics, as artworks – uniformly framed and tastefully hung against a strip of neutrally tinted hessian.28 Potted palms adorned the galleries, there were seats to rest and view the catalogue, designed in an art-nouveau style, and ladies served luncheons and afternoon teas. Harrington’s Photographic Journal commented on the ‘Australian atmosphere’ of so many of the entries,29 while the art critic and publisher Sydney Ure Smith wrote a flattering review for the Australasian Photo-Review, where he declared – in terms that now read as typically modernist – that ‘a beautiful photograph should look like a photograph, and not like a drawing. There are many beautiful qualities which a camera can suggest convincingly, such as an interesting pattern of foliage, tone values, decorative arrangement, and the rendering of textures and flat surfaces’.30 The presentation format was widely imitated over the following two decades and beyond (see for example, the 1926 Exhibition Gallery of the Southern Tasmanian Photographic Society).

The pictorialist style may have been visually formulaic, but through the continual circulation of their prints both nationally and internationally, Australia’s pictorialists were nonetheless able to enter into dialogue with other photographers as part of a dispersed community. Indeed, two Japanese-born photographers, Kiichiro Ishida and Ichiro Kagiyama, exhibited with the Photographic Society of New South Wales.31 Most importantly, the pictorialists pioneered the notion of the photography exhibition as art. 1922 advertisements for the annual exhibitions of the Photographic Society of NSW promote ‘Camera Art’ and ‘The Exhibition of Camera Pictures’ that ‘critics, connoisseurs and art lovers should not fail to visit’.32 Nevertheless, when the chairman of the board of the Art Gallery of New South Wales trustees, Sir John Sulman, opened the 1925 exhibition, he focused on photography’s accessibility:

Photography as it is practiced nowadays gives everybody a chance for self-expression … [and] fulfils a great need in the modern community; for very few people can afford to buy original works by painters and black-and-white artists; while through the unlimited reproduction that photography allows they can furnish their homes with pictures of taste and artistic merit.33

Sulman undoubtedly disappointed the audience by adding: ‘I am sorry that we have not space at the Art Gallery to house a collection of photographs. There is not the faintest hope of such a new department being started in my time, I fear, for we cannot find space there even to hang all our paintings’.34

Meanwhile, amateur salons proliferated well into the 1950s. The Victorian Salon of Photography in 1939 included 350 works from 22 countries.35 A reviewer of the 1957 Melbourne Camera Club International Exhibition at the Town Hall declared that ‘Every nation has contributed to this exhibition’, noting Chinese, Japanese, Indians and Malayans who, ‘[a]lthough latecomers to the white man’s invention … seem to understand the limitations of their medium much better than the Europeans’. The reviewer further claimed that while the exhibition ‘does not come into the category of art … it is nonetheless more interesting than most art shows. The camera-fiend is as much a hound for the unusual as the modern artist. He prefers bird’s-eye views or slug’s-eye views’.36 This long tradition of amateur exhibitions continues to this day, in a revised form, with events such as the Centre for Contemporary Photography’s annual open-entry salon.

-

‘Amateur Photographic Association’, North Melbourne Advertiser, 19 September 1890, p.3. ↩

-

The Age, Melbourne, 24 June 1884, p. 5. ↩

-

Mercury and Weekly Courier, Melbourne, 5 July 1884, p. 3. ↩

-

The Age, Melbourne, 24 June 1884, p. 5. ↩

-

The Argus, Melbourne, 24 June 1884, p. 4. ↩

-

The Argus, Melbourne, 27 June 1885, p. 5. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

The Age, Melbourne, 27 June 1885, p. 9. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

The Age, Melbourne, 7 December 1888, p. 6. ↩

-

Geelong Advertiser, 17 December 1894, p. 4. ↩

-

Geelong Advertiser, 19 April 1895, p. 2. ↩

-

Geelong Advertiser, 20 April 1895, p. 3. ↩

-

The Age, 22 April 1895, p. 6. ↩

-

Gael Newton, John Kauffmann: Art Photographer, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1996, p. 13. ↩

-

Newton, John Kauffmann, 1996, pp. 14–15. ↩

-

Gael Newton, Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839–1988, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1988, p. 70. ↩

-

Sydney Long, ‘An Artist’s Summing Up of the Pictures Exhibited at the N.S.W. Photographic Society’s Exhibition’, Australasian Photo-Review, 21 December 1903, pp. 442–6. T.W.C., ‘The Critic and the Late Photo Exhibition’, Australasian Photo-Review, 21 January 1904, p. 23. ↩

-

Newton, John Kauffmann, 1996, p. 13. ↩

-

‘The Element of Novelty’, Photograms of the Year, Iliffe & Son, London, 1911, p. 54. ↩

-

The Worker, 25 March 1909, p. 27. ↩

-

‘Photographic Exhibition – Harold Cazneaux’, Sydney Morning Herald, 16 March 1909, p. 6. ↩

-

Newton, Shades of Light, 1988, p. 84. ↩

-

‘One Man Show: Harold Cazneaux’, Australasian Photo-Review, 22 March 1909, p. 129. ↩

-

Sidney [sic] Long, ‘An Artists Summing up of the Pictures’, Australasian Photo-Review, 21 December 1903, p. 442. ↩

-

‘One Man Show: Harold Cazneaux’, p. 130. ↩

-

Newton, Shades of Light, 1988, p. 86. ↩

-

Some prints, however, were hung on the gallery’s columns, and art teacher and painter J. S. Watkins complained that the exhibition was a little too tightly hung. J. S. Watkins, ‘Exhibition of Australian Pictorial Photography’, Harrington’s Photographic Journal, Harrington & Co, Sydney, 20 December 1917, p. 377. ↩

-

‘Editorial’, Harrington’s Photographic Journal, 20 November 1917, p. 341. ↩

-

Sydney Ure Smith, ‘Some Notes on the Exhibits’, Australasian Photo-Review, 15 December 1917, p. 663. ↩

-

As Melissa Miles and Robin Gerster observe: ‘These two men were active members of the Photographic Society of NSW and regularly exhibited and published their work alongside leading Australian photographers at a time when the “White Australia” policy was testing diplomatic relations with Japan’. Pacific Exposures: Photography and the Australia-Japan Relationship, ANU Press, Canberra, 2018, p. 45. ↩

-

The Sun, 5 October 1922, p. 9. ↩

-

‘Photography Society’s Exhibition Varied Collection’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 June 1925, p. 16. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

‘A Comprehensive Exhibition’, The Age, 1939, p. 10. ↩

-

‘Artbursts’, The Bulletin, 3 April 1957. ↩