(Installation View, pp. 347–362)

From the 1980s, new possibilities for collecting and exhibiting photographs began to develop. Because each of these possibilities relied on emerging technologies, some were short lived, however they all left their mark on the exhibition practices, collection databases and the online audience interfaces of today’s galleries and museums. For instance, the current Museums Victoria online collection search interface links to 9163 images in a collection still called ‘The Biggest Family Album in Australia’. This collection was originally assembled between 1985 (the 150th anniversary of Victoria) and 1991, with museum staff – led by photography curator Euan McGillivray – spending two-week periods in different locations across regional Victoria, copying photographs from members of the public onto black-and-white negative film. The original owners kept their out-of-copyright photographs, but the museum became owners of the copy negatives. After being used for several books and a website, they became a definable subset within the museum’s online catalogue.1

In 1986, with funding from the New South Wales Council of the Bicentennial Authority, the NSW Government Printing Office transferred some of its collection of 200,000 negatives and 10,000 prints to 12 inch video laser discs (a technology similar to the audio CD). Once connected to a computer, the discs could be searched, images displayed on a monitor, and low-resolution prints made using a thermal printer. As the Printing Office helpfully explained:

The laser disc system uses a computer, a video monitor and new indexing. While previously it has been impossible to view anything more than a small part of the collection, through the laser disc system, the whole collection will become accessible. The system works like a video photo album, using the computer, you can search the disc in much the same way as you would a photo album, except that instead of seeing the image in prints, they appear on a video screen.2

Australia’s bicentenary in 1988 became the occasion for another video laser disc project, also funded by the NSW Council of the Bicentennial Authority. In a similar manner to Museums Victoria, the State Library of New South Wales (SLNSW) curator Alan Davies, and photographers Shayne Higson and Jenni Carter, spent the bicentennial year copying 7000 photographs from 600 people in twenty-four country New South Wales towns. The resulting black-and-white negatives were used for an exhibition and book, At Work and Play: Our Past in Pictures, and also recorded onto a searchable video laser disc available in the State Library’s main reading room. Davies described the basic condition for the public donation of photographs as, ‘Will this photograph be of interest to other Australians?’3

When the Printing Office finally closed in 1989, its original prints and negatives went to the New South Wales State Records, who had sufficient storage, but the video laser discs were transferred to the SLNSW, where they joined the At Work and Play video laser disc.4 Both sets of images were subsequently incorporated into the State Library’s online collections, where they are still accessible today. While the Government Printing Office collection was digitised from the video laser disc, and is therefore of low resolution, the State Library images were digitised from the 35 millimetre copy negatives and are of higher resolution.

Thirty years later, various techniques of ‘crowdsourcing’ continue to build archival collections at the same time as building audience relationships. For instance, in 2006 Martyn Jolly, co-author of this book, digitally reprinted personal photographs brought in by victims of the 2003 Canberra bushfires to create a collection of 600 brick-sized details, compiled into five glass columns standing at 3 metres tall for the ACT Bushfire Memorial. And in 2019, for the Museum of Sydney exhibition Street Photography, Sydney Living Museums and the photographer Anne Zahalka put out a call on social media for the citizens of Sydney to bring in the photographs taken of them by the commercial ‘street photographers’ who worked the streets, taking candid portraits from the 1930s to the 1950s.

Meanwhile, the idea of a collection that exclusively exists online continued to develop. In September 2000 the National Library of Australia (NLA) launched Picture Australia, which brought together digitised images from cultural heritage collections, while also sourcing contemporary images from a series of groups on the then popular photo-sharing site Flickr. As in the earlier democratic projects of Museums Victoria and the SLNSW, the Flickr groups ‘ensured individual contributions to Picture Australia were included in the snapshot of Australiana’.5 In 2012, Picture Australia was integrated into Trove, the online content aggregator that had been launched by the NLA in 2009. The original idea of individual photographers contributing their photographs to ‘a snapshot of Australia’ now continues as a ‘Trove: Australia in Pictures’ group on the, by now much less popular, Flickr site, and as a #Flickr tag within the ‘Images, Maps and Artefacts’ category of Trove.

While democratic photo-sharing sites such as Flickr are beginning to lose some of their importance in the online space of contemporary photography, other photography apps are continuing to grow in importance, and are used not just by enthusiasts, but by established contemporary photographers. Artists such as Katrin Koenning, Hoda Afshar, Prue Stent and Lee Grant, for instance, each have tens of thousands of Instagram followers who have ongoing relationships with their sophisticated photographic practices that live beyond the exhibition, the gallery or the collection – and yet inevitably inform and help promote more traditional exhibition and publication practices.

Institutions have also begun to build databases of the work of individual photographers at a massive scale. For instance, Tasmanian wilderness photographer Peter Dombrovskis is extremely significant to Australia’s conservation movement, with his photograph Morning Mist, Rock Island Bend, Franklin River, Tasmania, 1979, used as the virtual logo of the political campaign to save the Franklin River in 1982. The image was included in a 1982 touring exhibition devoted to the issue. ‘Lush in colour and cloyingly sentimental in style’, as Geoffrey Batchen notes, Dombrovskis’s photographs were ‘the most conservative-looking images in the exhibition’.6 But thanks to his friend, the activist Bob Brown, and the Tasmanian Wilderness Society, Morning Mist became one of the most politically potent photographs in Australian history. It was used in posters and run as a full-colour, double-page advertisement in every major newspaper on the eve of the 1983 federal election under the slogan, ‘Could you vote for a party that will destroy this?’7 Nevertheless, Dombrovskis’s work was not extensively exhibited in contemporary art galleries until recently. As the curator Matthew Jones notes, ‘most Australians encounter his photographs for the first time in quite prosaic settings: in a diary used at work, a calendar on the side of the fridge or a poster in a waiting room’.8

Art institutions only collected Dombrovskis’ prints on a relatively small scale: in 1985 the National Gallery of Victoria purchased five Cibachrome darkroom enlargements printed from his large format transparencies by his long-time collaborator Ralph Hope-Johnstone, and in 2002 the National Gallery of Australia carefully selected seven colour darkroom enlargements. But five years later, the NLA purchased almost his complete archive, 3495 transparencies in all, from his widow. The transparencies were scanned with custom-made colour profiles before they were placed in cold storage. The entire collection of new scans was placed online as scalable files where, after searching for a subject, the user could zoom into the microscopic detail and adjust the contrast of each image. In 2017, as the earlier darkroom enlargements in the collections of galleries would have been beginning to show shifts in colour due to their age, the NLA made seventy pristine digital prints from the new scans for a touring exhibition.

Dombrovskis died in 1996, but museums are increasingly entering into long-term relationships with living photographers. In this new environment of digital mutability, what is transacted between a photographer and the institution is now not so much a print, or even a negative, but the use of a digital file. The digital space becomes a zone of contact between photographer and exhibition. Photography exhibitions are now emailed around the world, while photography festivals such as the Pingyao International Photography Festival print the files supplied by their exhibitors and destroy the prints afterwards to minimise freight costs. This can lead to unexpected exhibition practices. For instance, in 2014, Tracks surf magazine photographer John Witzig worked with a photographer from the National Portrait Gallery who scanned and digitally printed his 35 millimetre negatives from the 1970s for the touring exhibition Arcadia. To be able to generate large ‘hero pictures’ for the walls of the exhibition, digital grain was added to the initial scan from the small, less-than-sharp 35 millimetre negatives.

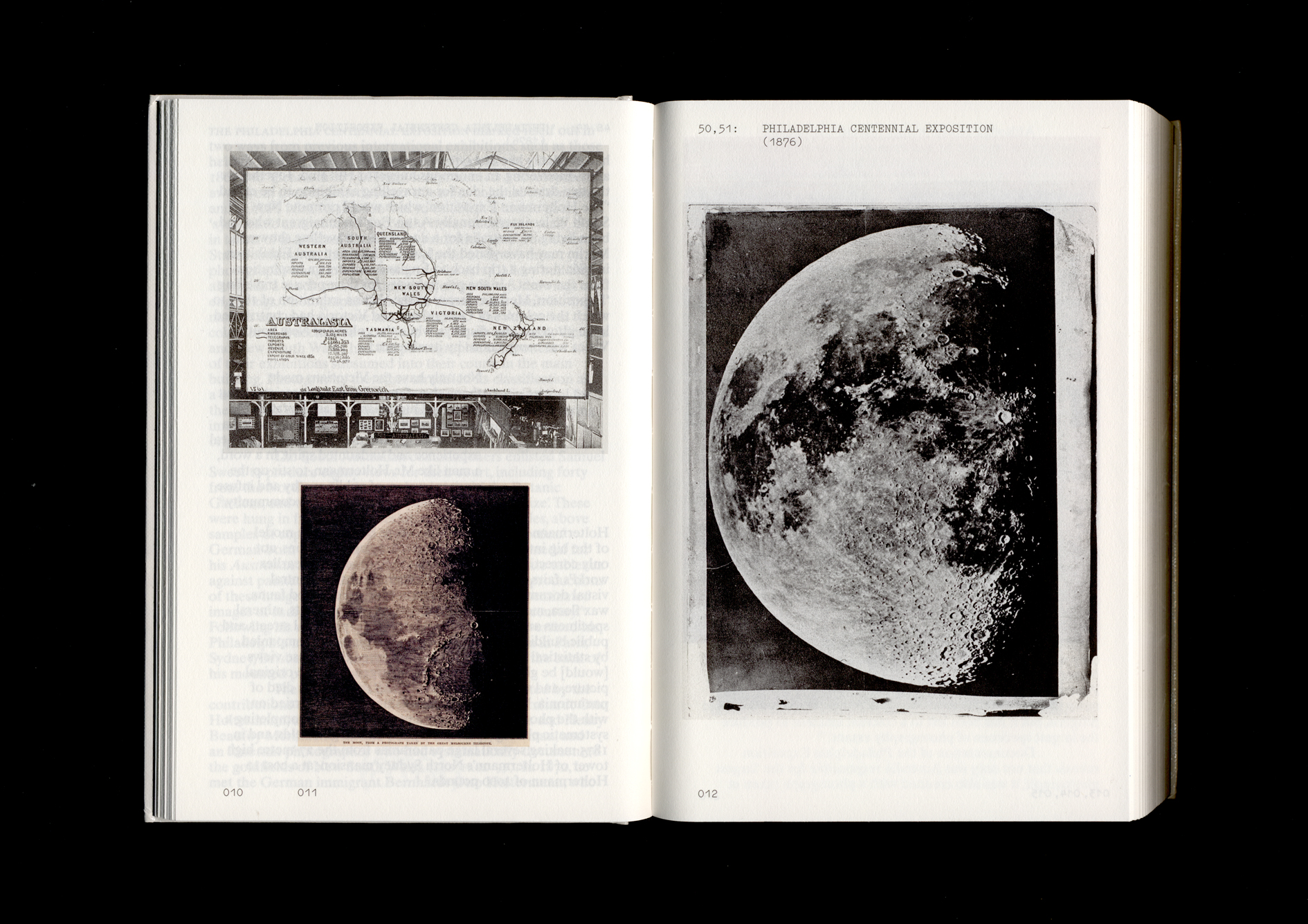

For the 2012 touring exhibition Remember Me: The Lost Diggers of Vignacourt, which was based on a collection of 800 glass plate negatives of Australian soldiers made at a World War I-era French portrait studio and donated by the Australian businessman Kerry Stokes, the Australian War Memorial made beautiful, fibre-based selenium-toned prints, handcrafted ‘in the old fashioned way in the darkroom’. Although few other museums or galleries have had the resources to produce this sine qua non of the art photography tradition – the selenium-toned, handcrafted print – in house, they have nonetheless increasingly generated print and online exhibitions from their negative archives using digital technology. For instance, between 2008 and 2011 the SLNSW, with its curator Alan Davies who had previously initiated the bicentennial video laser disc project, scanned 3500 negatives made on the goldfields by Beaufoy Merlin and Charles Bayliss, which had been partially displayed at the Philadelphia Exhibition in 1876 and then rediscovered and acquired in 1952 as the ‘Holtermann Collection’. The smaller negatives were scanned on a flatbed scanner, while the mammoth plates were photographed in sections by medium format digital cameras and stitched together. To Alan Davies, this digital release of data finally realised the ultimate destiny of the historic photograph: ‘For the first time in 140 years, it is possible to see what Beaufoy Merlin and Charles Bayliss photographed, with astonishing clarity and fidelity. It is now feasible to read nineteenth-century posters on a distant wall, the labels on bottles in a pharmacy window, and to identify individuals in the crowd’.9

In the resulting online exhibition, viewers can zoom in and track across the images in extraordinary detail with their cursors, while pop-ups provide helpful comments. One of the many delights of exploring scanned photographs online in such recent exhibitions as Capturing Nature: Early Scientific Photography at the Australian Museum 1857–1893 is to experience the swirls and eddies at the edges of the hand poured collodion emulsion, and the chips and cracks in the glass, which shift attention from the photograph as mere ‘image’ (visual data) to the photograph as ‘artefact’ (a material thing). But, as the user zooms and pans online, the artefact dematerialises, and the user falls once more into the virtual space of the image.

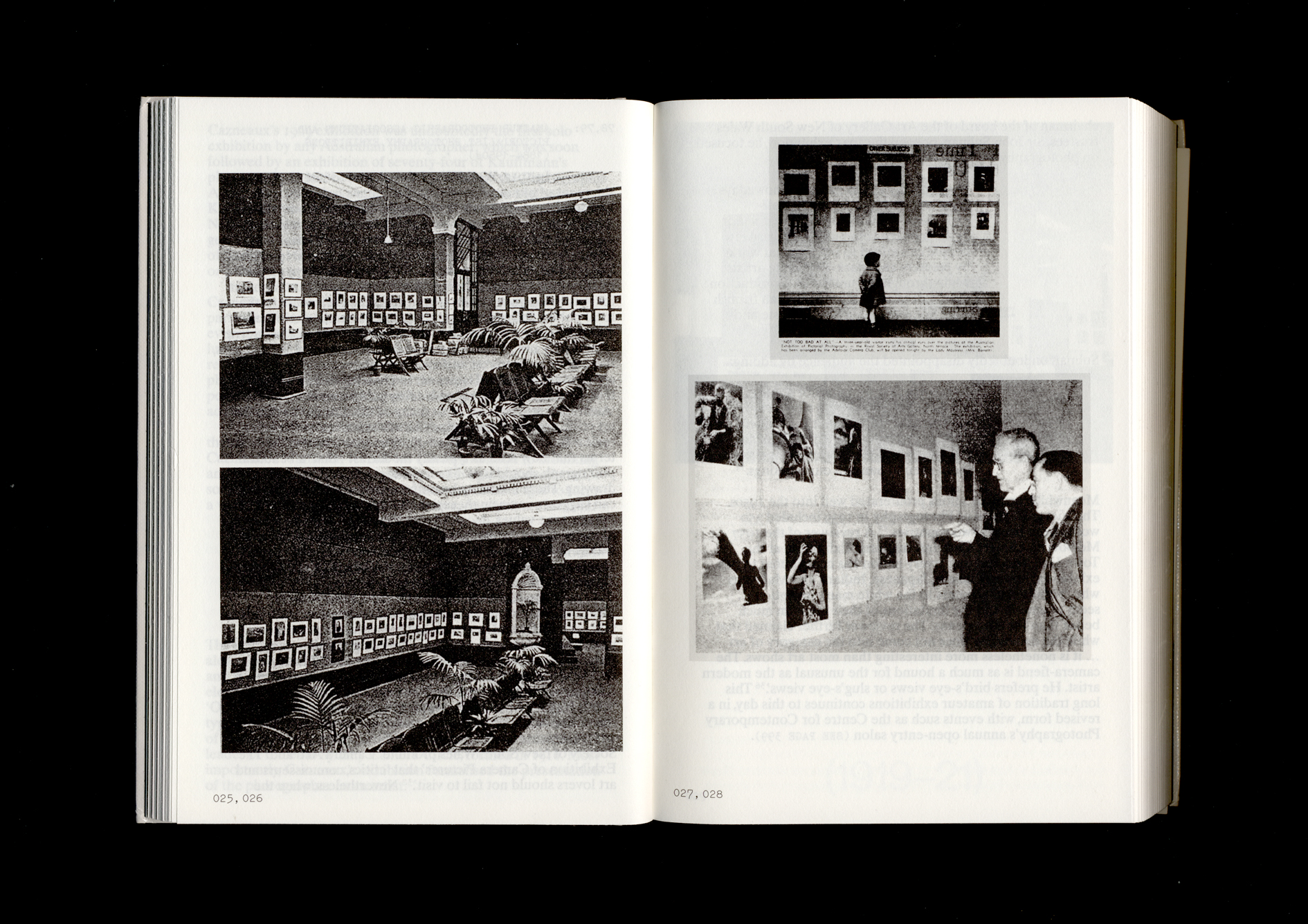

As established by two now classic international books of archival photography, both called Evidence,10 the dramaturgy of the archive is played out with particular power in forensic archives. In 1992, Ewa Narkiewicz printed historic glass negatives lent by the Police Forensic Laboratory for the Victorian Centre for Photography’s (VCP) After the Fact: Photographs from the Police Forensic Archive, curated by Susan Fereday from the VCP and Christine Downer from the State Library of Victoria (SLV). The original context of the images had been lost, but the curators were interested in the ‘vacant street scenes and empty places which appear to be filled with narrative significance’.11 Undoubtedly, no archive has been as productive as the New South Wales Police Forensic Photography Archive of 130,000 negatives, taken between 1910 and 1964, and rescued from a flood in 1990 to become part of The Justice and Police Museum. In 1999, the museum produced its first exhibition from the archive, Crime Scene: Scientific Investigation Bureau Archives 1945–1960, curated by Ross Gibson and Kate Richards; followed by City of Shadows: Inner-City Crime and Mayhem 1912–1948, curated by Peter Doyle in 2005; and Underworld: Mugshots from the Roaring Twenties, curated by Nerida Campbell in 2018.

After the 1999 exhibition, Ross Gibson and Kate Richards continued to produce interactive electronic art based on the archive, which they dubbed ‘Life After Wartime’, which developed alongside advances in technologies of audience engagement. Gibson explained how sudden encounters within the archive itself drove him to embrace interaction and immersion. As he wrote in 1999:

I need to compose a volatile sound + image device that mimics the dramatic sequencing that plays out when one encounters the photographs and feels one’s senses sharpen to pain or dull down to an ache. I want to help the viewer register the pulse in these pictures and thereby experience all the flashing and sluicing emotions which attend that pulse.12

Gibson and Richards developed a database of 3000 images from the archive combined with thousands of short poetical texts from Gibson. Using metadata, they could search and collate images and texts, and iterate image/text combinations. In 1999, they produced Life After Wartime, an interactive CD-ROM that used Macromedia Director and ‘fuzzy logic’ to generate a series of loose narrative chunks out of the database. When a version was shown at the Centre for Contemporary Photography’s e-Media Gallery in 2001 (under the title Darkness Loiters), a wall with letterbox slits was built in front of the monitor, requiring viewers to peer through to see the screen. Subsequent iterations included a live improvisation performance at the Opera House in 2003 where, using VJ software, the artists selected images and texts live from the database and projected them behind the experimental jazz trio The Necks; and Bystander, a five-channel interactive and immersive video installation in 2006. In Bystander, visitors entered a room comprising five projection screens with surround-sound audio. The room became what the artists called ‘a performative story-generator’, where computer software composed a ‘spirit world’ of photographs, texts and sound in response to the movement of visitors.13

While Gibson and Richards built their own database, more recently artists have turned to the seemingly infinite archive of photographs available on the internet. Artists are exploring and critiquing the algorithmic processes of searching, filtering and selecting which are now fundamental to not only online photography libraries, but also shopping sites such as eBay, and search engines such as Google Images. For instance, to conclude the major Art Gallery of New South Wales survey exhibition The Photograph and Australia in 2015, curator Judy Annear commissioned Patrick Pound and Rowan McNaught to build The Compound Lens Project, where custom software perpetually, and poetically, searched, selected and graphically interpreted online photographs for the audience. Such experimental projects propose new ways of curating in the age of online photo-sharing, and often persist after the physical exhibition has ended.

Libraries and museums now routinely work in the area of digital photographic displays. For instance, in 2015 SLNSW established its DX Lab which, through various experiments with data visualisation and digital technologies, develops new ways to interface with the library’s data sets, collections and services. In 2020 they launched an experimental interface to their digitised collections. Designed by Mauricio Giraldo, Aereo graphically displays the collections as a whole, rather than a list of discrete items or files retrieved response to a keyword search. In 2019, the State Library of Queensland developed the ‘Corley Explorer’ with Mitchell Whitelaw and Geoff Hinchcliffe, which allows online visitors to navigate, locate, tag and annotate the 61,000 photographs taken by Frank and Eunice Corley who, like the street photographers of Sydney, drove the suburban streets of Queensland from the 1960s to the 1970s taking photographs of houses to sell to homeowners. Even the Australian War Memorial has returned to their origins from around the period of World War I in an online project called Art of Nation: Australia’s Official Art and Photography of the First World War. The curators built a virtual memorial from early plans sketched by the War Memorial’s founder C. E. W. Bean, in which online visitors can mount the grand steps, enter the neoclassical building and encounter the famous photographs of Hurley and Wilkins on the walls, and even witness a schematic magic lantern show.

The imaginative archival space created by these recent experiments is no longer the ‘video photo album’ as had been imagined in the digital incunabula of the 1980s, but a multidimensional space of interpenetrating virtual architectures, where users navigate, track, pan and zoom. Yet from the 1980s until the present, the same tensions remain – between image and artefact, between the original photographer’s intention and the end user’s experience, and between the affordances of the database and the curiosity of the user.

-

‘The Biggest Family Album in Australia’ Collection’, Museums Victoria. Online at: https://collections.museumvictoria.com.au/articles/2975. Accessed 1 July 2019. ↩

-

Priceless Pictures: From the Remarkable NSW Government Printing Office Collection 1870–1950, NSW Government Printing Office, Sydney, 1988, p. 6. ↩

-

Alan Davies, At Work and play: Our Past in Pictures, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1989, p. 5. ↩

-

Jesse Adams Stein, Precarious Printers: Labour, technology & material culture at the NSW Government Printing Office 1959–1989, PhD thesis, University of Technology Sydney, 2014, pp. 66–7. ↩

-

‘Australian Pictures in Trove’, Online at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/. Accessed 18 June 2019. ↩

-

Geoffrey Batchen, ‘Australian Made’, Afterimage, May 1989, p. 17. ↩

-

See: Gael Newton, ‘Time, Place and Exposure: Understanding Peter Dombrovskis’, in Liz Dombrovskis (ed.), Simply: Peter Dombrovskis, West Wind Press, Sandy Island, 2006. According to Newton, Bob Brown first published Rock Island Bend as the attachment to a letter to The Australian newspaper. ↩

-

The Photography of Peter Dombrovskis: Journeys into the Wild, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2017, p. 145. ↩

-

Alan Davies, The Greatest Wonder of the World, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 2013, p. 22. ↩

-

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel, Evidence, Clatworthy Colorvues, Greenbrae, California, 1977; Luc Sante, Evidence, Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York, 1992. ↩

-

Flyer for After the Fact: Photographs from the Police Forensic Archive, Victorian Centre for Photography, Melbourne, 1992. ↩

-

Ross Gibson, ‘Negative Truth: A New Approach to Photographic Storytelling’ Photofile, vol. 58, 1999, p. 31. ↩

-

Authors’ correspondence with the artists. ↩