(Installation View, pp. 261–272)

One of the defining features of postmodernism in the visual arts is that artists who had never had any technical training in the photography were drawn to using the medium. Where conceptual artists in the 1970s had sometimes turned to snapshot photography for its ‘dumb’ qualities and the potential of the serial format, by the turn of the new decade artists and curators were turning to the camera as a privileged vehicle to comment on issues of representation. Judy Annear’s exhibition Frame of Reference at the George Paton Gallery in 1980 – supported and toured by the Australian Gallery Directors Council – sits at the cusp of the transition from conceptual art to postmodernism and the prevalence of ‘artists working with photography’. As Annear wrote in the exhibition catalogue, Frame of Reference brought together twelve Australian artists ‘whose work in photography comes less from formal training in that area and more from a questioning of the medium … and photography’s meaning in society’. The exhibition included Virginia Coventry, Richard Dunn, David Francis, Ian de Gruchy, Adrian Hall, Angela Larusso, John Lethbridge, Robert Owen, Gareth Sansom, Lynn Silverman, Alan Spackman and John Young, each working in a wide variety of styles and formats.

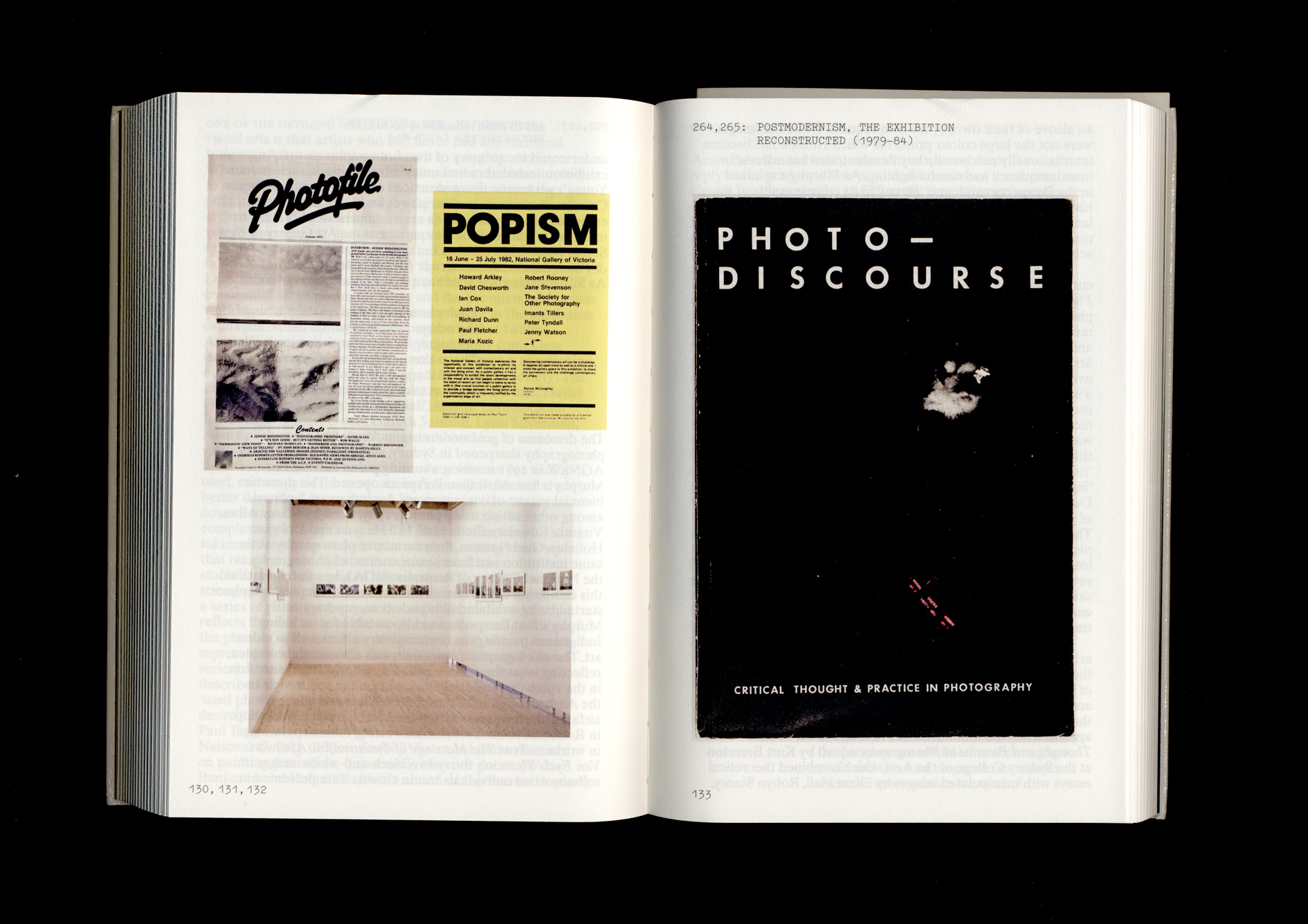

In 1980, the term postmodern was not yet widely used, and many of the artworks in Frame of Reference are better described as conceptual. For instance, the catalogue cover featured Robert Owen’s Apposition, 1979–80, – a complex work comprising a set of fifteen Polaroids of a stool taken as the sun moved past the window, casting shadows that rotate around the stool’s axis; an installation of fifteen stools arranged in a grid of three rows of five and lit with a strong spot that casts their shadows clearly on the floor; and a series of paintings hung on the wall behind the stools that reflects the real scale of the stools but in the configuration of the photos (a juxtaposition of document with object and its representation that recalls Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three series). Others artists in Frame of Reference are properly described as postmodern, such as John Lethbridge, who ‘used photography to construct and deconstruct codes of desire’.1 However, it would be another two years before Paul Taylor’s landmark Popism exhibition was shown at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) – an exhibition focused on painting, but whose theoretical reference points – Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes’s notion of the ‘second degree’ – underscored the primary of the photographic on art. Annear’s exhibition included more earnest investigations, such as Virginia Coventry’s documentary series on nuclear power and Lynn Silverman’s exploration of the horizon in the Australian landscape (a series Annear would return to many years while senior curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), in her 2011 exhibition Photography & Place: Australian Landscape Photography 1970s Until Now). As Silverman’s artist statement in the catalogue contends:

Each photograph derives its meaning from the others around it within the series. The photographs all comment on each other … These alternatives give larger scope for the use of the photographic medium/material, and not taking the camera for granted as a ‘natural’ recorder of ‘reality’.2

The discourse of postmodernism in Australian art and photography sharpened in Sydney, with two exhibitions at AGNSW in 1981 marking a turning point. In May, Bernice Murphy’s first Australian Perspecta opened. This dynamic biennial survey of contemporary Australian art featured, among other artists using photography, work by Micky Allan, Virginia Coventry, Fiona Hall, Bill Henson and Douglas Holleley. Gael Newton, then curator of photography at the same institution and later senior curator of photography at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), has since identified this exhibition as the critical moment when ‘art photographers started being exhibited alongside contemporary art’.3 Murphy’s first Perspecta was also notable for including Indigenous paintings as contemporary art, as well as video art. The photographic component was eclectic and complex, reflecting what the curator called ‘a richer cultural situation in the 1980s’ borne of developments in the 1970s such as the Australia Council, vibrant art schools and cheaper airfares.4 Hall was fresh from the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York, reconstructing famous paintings in works such as The Marriage of the Arnolfini: After Jan Van Eyck. Henson’s thirty-two black-and-white images of self-absorbed individuals lost in crowds were presented in an alcove of their own, by his own request. While the images were not the large colour prints for which Henson has become internationally renowned, they demonstrated his interest in mood, sequence and careful lighting. As Murphy explained in the Perspecta catalogue: ‘Strong in its consciousness of the history of art, Untitled Sequence is deeply informed also by the language of film and employs a non-narrative formal structure than has strong analogies with a major piece of music. A rare achievement in photography!’5

A few months later at the same institution, Newton curated Reconstructed Vision: Contemporary Work with Photography, including thirty-six artists who all broke from photography’s realist traditions. The roster extended from recent art school graduates such as Fiona Hall to Micky Allan and the experimental work of an older generation such as Mark Strizic, who made photograms printed through paraffin wax overlaid with drawing. The exhibition was premised, in short, on a new wave of manipulated work in contemporary photography, including photomontage, handcolouring and other alternative techniques. The modernist photographer Max Dupain, who was then writing newspapers reviews, was scathing. In a review titled ‘Exhibitors, stop it or you may go blind’, he called it ‘reconstituted photography’, ‘insular introspection’ and an ‘ingrowing toenail of an exhibition’ by ‘photo psychos’.6 For Dupain, the exhibition was ‘self-indulgence, making a mockery of photographic life and … must surely be classified trivia’. The stakes were personal – Dupain had first protested against pictorial photography in a letter to the same newspaper over an international survey exhibition in 1938 (not long after which he severed his own flirtation with surrealist photomontage), and he saw this new development in 1981 (forty-three years later) as a corruption of ‘straight camera technique’ – for him the authentic trajectory of modernist photography.

But Dupain was raging against a storm. The Sydney art scene was now a hotbed of postmodernism, influenced by the translations of French theory emerging out of the University of Sydney. A plethora of art magazines, including Art Network and On the Beach, were avenues where writers could apply this theory to photographic exhibitions. Aspects of this philosophical approach filtered into the book Photodiscourse: Critical Thought and Practice in Photography edited by Kurt Brereton at the Sydney College of the Arts, which combined theoretical essays with manipulated images by Fiona Hall, Robyn Stacey, Anne Zahalka and many others from around Australia – a direct reply to the perceived fine print conservatism of the Australian Centre for Photography (ACP) at the time. Newton’s catalogue essay for Reconstructed Vision was widely cited in the 1980s, influencing exhibitions as far afield as Brisbane and Hobart, such as Extended Landscapes at the Tasmanian School of Art Gallery in 1983, which featured the constructed panoramas of David Stephenson, newly arrived as a lecturer from the US. When Dupain, as elder statesman, was invited to launch the inaugural exhibition of photography at the newly opened NGA in Canberra in 1982, according to Isobel Crombie, who was a curator there at the time, ‘he used the occasion to forcefully condemn contemporary Australian photography as being “too arty”’.7 As Crombie reflected in 2010: ‘He was right to conclude that the dominant fine print ethos was under attack by artists who manipulated the medium in various ways’.8 Confirming the direction Australian art was heading, Henson, Hall and Sue Ford became the first Australian photographers to be represented in a Sydney Biennale in 1982. Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery opened in the same year and became the most influential commercial gallery representing postmodern art photographers – eventually including Henson, Zahalka, Tracey Moffatt, Julie Rrap, Destiny Deacon and Patricia Piccinini.

The exemplary solo photography exhibition during this period was Julie Rrap’s first show, Disclosures: A Photographic Construct, at Central Street Gallery, Sydney in April and May 1982. Then known as Julie Brown, Disclosures took the form of a complex and layered installation comprising sixty black-and-white and nineteen colour Cibachromes hanging freely from the ceiling of a narrow room, some of which swayed gently as the viewer walked through them. As the artist John Delacour wrote in his review:

The installation constitutes a decisive break with exhibition orthodoxy, perhaps best exemplified by the Australian Centre for Photography gallery – it is impossible to imagine Brown’s show in that space where the pictures are confined to the magnetic walls and the cool elegance neutralises even the most subversive work. At Central Street two corridors of facing images were suspended from the ceiling on fishing line.9

On one side were photographs of the artist’s studio, shot by self-timer from a camera strung around Rrap’s neck, and on the other side, photographs of the artist’s life-sized naked body shot in the same moment by a camera on a tripod on the other side of the studio. As Delacour argued, standing between the two rows, the viewer ‘as voyeur is positioned between the two cameras and subjected to their interrogating gaze’.10 Rrap’s background lay in conceptual and performance art, and by turning the camera on herself Disclosures initiated the notion of performance documentation as a powerful medium for feminist art.11 Rrap was among the first to take up French post-structuralist theory in art photography, building on the feminist analysis of sexual politics that had gained strength in the 1970s around groups such as the Blatant Image. As the feminist art historian Catriona Moore has argued, Disclosures ‘took the spectator into a strenuous, disciplinary “workshop” on studio photography’ in which they lose control ‘over the image of woman through the fractured visual field’.12 As Delacour put it, ‘the active engagement with the pictures necessary to decipher their structural code denies the audience the passive consumption associated with single pictures on a wall’. The process was further complicated by the artist’s presence in the gallery throughout the duration of the show.

Disclosures was a precursor to a series of exhibitions by Rrap exploring the representation of women. Rrap was included in Bernice Murphy’s second Perspecta in 1983, the first to mention the term ‘postmodernism’.13 Meanwhile, the ACP under new director Tamara Winikoff was attempting to embrace a broader community, and established the newspaper Photofile in 1983, which became a vehicle for theoretical debate following its transformation into a critical journal, most effectively under Geoffrey Batchen’s tenure as editor between 1985–86. By this time, photography as a medium had become an arena in which wider debates about representation, simulation, gender and power were being energetically played out. The visual language of popular culture, such as advertising and film, as well as painting and especially surrealism, were all open for raiding by artists, for parody or allegory. For instance, Rrap’s exhibitions engaged increasingly with the representation of women’s bodies in art history, beginning with the Persona and Shadow series exhibited at George Paton and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery in 1984. The life-size Cibachrome images that make up the series are nearly 2 metres tall and 1 metre wide, echoing the physical scale of the European paintings of female nudes that inspired them. Photography had suddenly become the avant-garde of Australian art, and photographs grew in size and ambition accordingly, enabled by the availability of new printing processes and a new audience of contemporary art critics, curators and collectors.

-

See: Judy Annear, ‘Not Careful’, in Helen Vivian (ed.), When You Think About Art: The Ewing and George Paton Galleries, 1971–2008, Macmillan Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2008, pp. 62–81. ↩

-

Frame of Reference, exhibition catalogue, George Paton Gallery, Melbourne, 1980. ↩

-

Newton was asked in a 2014 interview with Lynette Letic: ‘How have you seen the evolution of Australian photography expand and shift over the past decade?’ She responded, ‘Well the biggest change was when art photographers started being exhibited alongside contemporary art and that I date quite specifically to Bernice Murphy’s first Perspecta exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1981. There had been a division before of artists who used photography and ‘photographers’ who were seen as nice in their own way but not serious ‘contemporary art’. Interview reprinted on Gael Newton’s website, Photo-Web. Online at: http://www.photo-web.com.au/gael/docs/QCP-interview.htm. Accessed 28 October 2019. ↩

-

Bernice Murphy, Australian Perspecta 1981: A Biennial Survey of Contemporary Australian Art, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1981, p. 33. ↩

-

ibid., p. 89. ↩

-

Max Dupain, ‘Exhibitors, Stop It or You May Go Blind’, Sydney Morning Herald, 4 August 1983. Also quoted in Joanna Mendelssohn, Alison Inglis, Catherine De Lorenzo and Catherine Speck, Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening Our Eyes, Thames and Hudson, Melbourne, 2018, p. 88. ↩

-

Isobel Crombie, ‘Commentary’, in Anne Marsh (ed.), Look: Contemporary Australian Photography Since 1980, Macmillan Art Publishing, Melbourne, 2010, p. 386. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

John Delacour, ‘Julie Brown’s Disclosures – In Context, out of the Biennale’, Art Network no. 7, 1982, p. 34. Delacour contrasted Rrap’s work with the photographic work in the concurrent Biennale of Sydney, contrasting her layered installation favourably against photographs ‘framed and lined up like ducks on the wall’ and the ‘puerile obsession’ with ‘the integrity of the single image’. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Julie Rrap, Disclosures, 1982, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney. Online at: https://www.mca.com.au/artists-works/works/1994.23A-AAAA/. Accessed 30 August 2019. ↩

-

Catriona Moore, Indecent Exposures: Twenty Years of Feminist Photography, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p. 129. ↩

-

Other photographers in the 1983 Perspecta included David Stephenson and Miriam Stannage, based in Hobart and Perth respectively. ↩