( Installation View, pp. 47–56.)

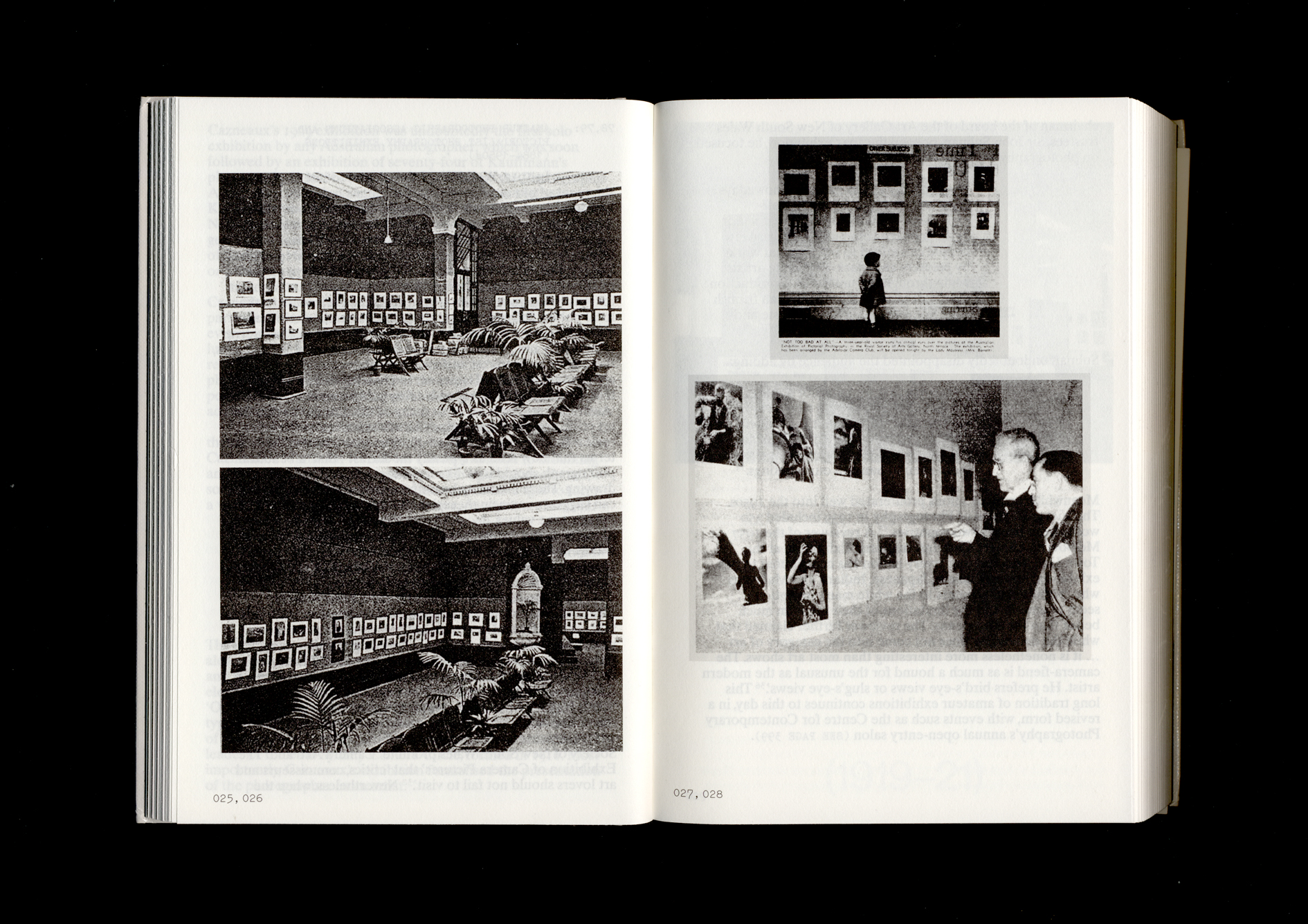

The Philadelphia Centennial Exposition marked itself out in two ways from previous international exhibitions, such as those held in London in 1851 and 1862, New York in 1853, Paris in 1867 and Vienna in 1873. Firstly, it represented a development away from the congested clutter of earlier colonial exhibitions and world’s fairs. Its mission was to establish a ‘stable gaze’, ‘systematic and tabular’.1 Secondly, it was massive in scale, both in terms of individual objects and exhibition area. The United States contingent, for example, displayed no fewer than 137,145 photographs hung in an extension to the Art Gallery building, alongside a much smaller number of oil paintings, drawings and engravings. Photography from three dozen other contributing nations and colonies were also on display.2 The Australian colonies of Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales had the photographic component of their exhibitions subsumed into their courts in the main building. Photography therefore straddled its classification as a mechanical art, and its function as a contextualising tool for the displays of commodities and manufactured wares, offering images of the locations where resources and goods were originally produced.

The South Australian commissioners enlisted Samuel Sweet to produce eighty views for their court, including forty from the Northern Territory, twenty-eight of the Botanic Gardens, and twelve landscapes, ‘all of convenient size’. These were hung in framed grids beside tanned animal hides, above samples of copper ore, and behind banks of wine bottles.3 German-born photographer J. W. Lindt won a gold medal for his Australian Aboriginals, 1873–74, posed in elaborate tableaux against painted backdrops in his Grafton studio. Reproductions of these images became among the most widely disseminated images of Indigenous Australians in the nineteenth century.4 Following his move to Melbourne in 1876, Lindt advertised his Philadelphia medal, along with other medals he won in Paris, Sydney, Brisbane and Sandhurst (now Bendigo) on the back of his mounted photographs.

The New South Wales Court was dominated by the contributions of three men: the financial backer Bernhardt Otto Holtermann, and the photographers Charles Bayliss and Henry Beaufoy Merlin. Merlin had been a travelling showman, and an itinerant photographer who had systematically documented the goldfields of New South Wales. In 1872, he met the German immigrant Bernhardt Otto Holtermann, who had suddenly become one of the wealthiest men in Australia after discovering an enormous nugget at Hill End. Together the two devised the idea for a travelling exhibition to be called ‘The Holtermann Exposition’, which would promote New South Wales internationally. As an English immigrant who had been living in Australia for a decade as a travelling showman, Merlin may have visited the London International Exhibition in 1862 during a trip back to England and drawn inspiration from the event.5 In the pre-publicity for their private travelling ‘Exposition’, Merlin referred to the Vienna exhibition of 1873 to which the colonies of Queensland and Victoria had contributed large photographic displays, while the colony of New South Wales was conspicuous by its absence:

Not only have the Victorians made themselves famous to our depreciation, but even the Queenslanders are imitating the example of the latter. It certainly needed a man of energy and means, a man of practical experience and undaunted spirit, in a word, a man like Mr. Holtermann, to stir up the stagnant waters of public apathy and infuse a little go-a-head-ism into this community.6

Holtermann and Merlin’s plans were based on the model of the big international and intercolonial exhibitions, not only correcting New South Wales’s absence from earlier world’s fairs, but also using photography as the central visual document. They planned to tour taxidermied fauna, wax flora, mechanical models, agricultural products, mineral specimens and photographic views of the principal streets and public buildings of every town in the colony – accompanied by statistical information. They proposed that ‘these views [would] be glass transparencies, enlarged from the original picture, and vividly coloured.’7 In late 1873 Merlin died of pneumonia. Nevertheless, his assistant, Bayliss, carried on with the photography component of the project, completing a systematic photographic survey of colonial goldfields, and in 1875 making several large panoramas from the 27-metre high tower of Holtermann’s North Sydney mansion, at a cost to Holtermann of 4000 pounds.8

Although Holtermann’s private ‘Exposition’ did not get the support he had expected from his fellow colonists or the colonial government, Holtermann himself took Merlin and Bayliss’ photographs, as well as Bayliss’ panoramas mounted on canvas, to Philadelphia in 1876 and then to the Paris Universal Exposition in 1878. Bayliss’s 10-metre-wide Panorama of Sydney Harbour, and Suburbs overlooked the New South Wales Court in Philadelphia. It was placed alongside a large rectangular prism or ‘trophy’ that represented the weight and value of gold found in the colony. The panorama is framed along the top by two rows of photographic views of the government and commercial buildings of central Sydney, landmarks that would have been barely visible in their detail above the expansive installation. The panorama covers a six-kilometre stretch of the Harbour and surrounding foreshore.9 Holtermann’s benefaction allowed Bayliss to buy a superior German large-format camera from which he took the twenty-three negatives, each 50 x 40 centimetres in size, the contact prints from which were butted together to make up the panorama.10

Scanning the work, a visitor to the exhibition may have been unsettled by what Helen Ennis has called the curious ‘spaciousness’ of Bayliss’s photography.11 On account of the increased exposure time of the giant plates and long focal length lenses, not one silhouette or human outline is discernible in the expanse of harbour, residential homes, horses grazing and blurred linen fluttering in the breeze. An astute visitor may have noticed how the shadow falls unevenly, between plates, as time had passed between exposures. More likely, though, the onlooker would simply have been in awe of the giant panorama’s sweep – a new triumph in the view trade. Holtermann’s plates were not the largest at Philadelphia though; the American photographers also exhibited their mammoth single-plate landscapes of the West. and as such Holtermann only won a bronze medal, not the gold medal he had expected.12 Nevertheless, news of Holtermann’s panorama, the ‘Largest Photograph in the World’, travelled widely. A Californian newspaper reported that ‘the art of photography has made rapid progress, but it has been left to a colonial amateur to produce the largest specimen of photography extant’.13

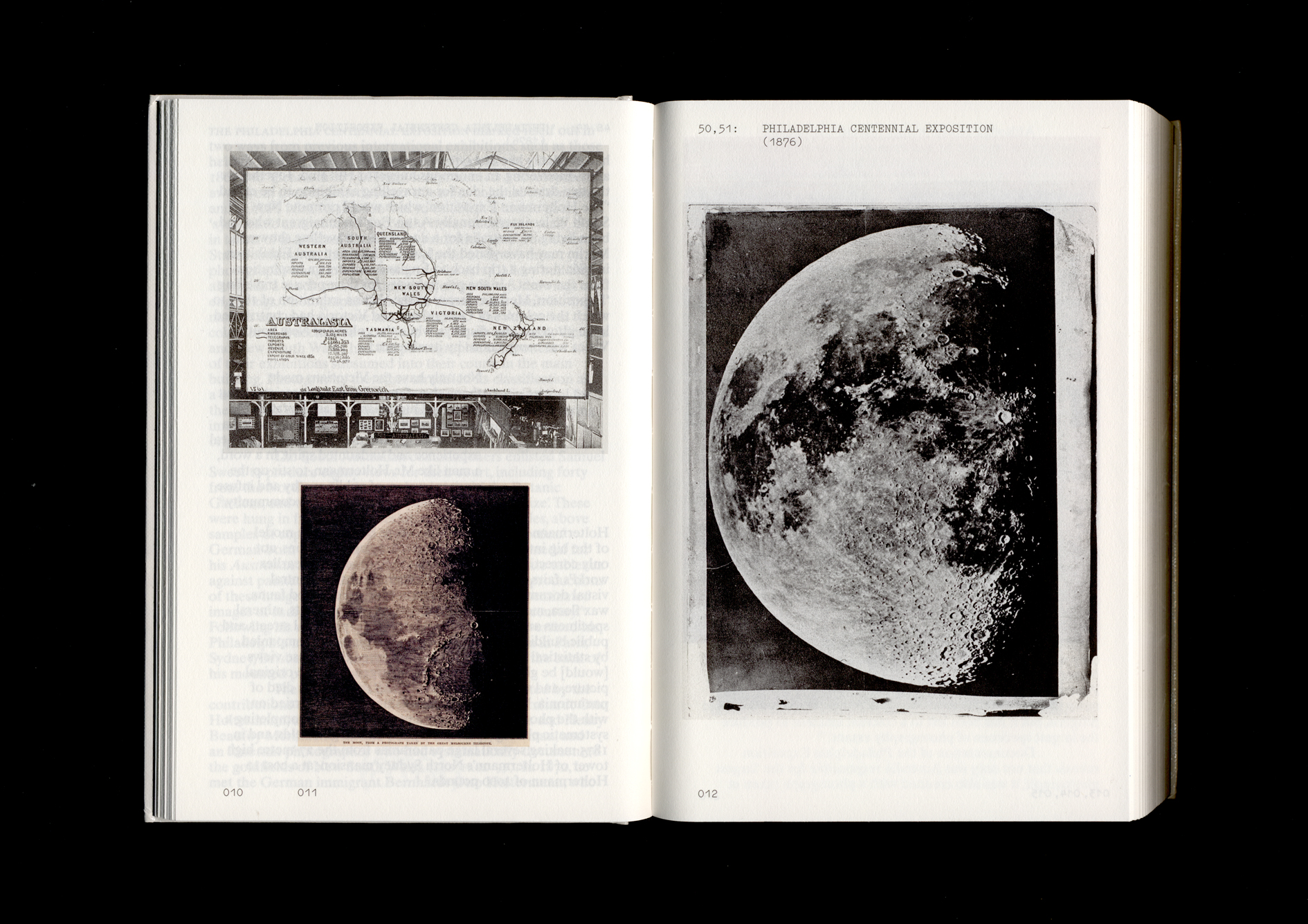

Documentation of the Philadelphia Exposition reveals that not only was Australia responsible for the ‘largest photograph’, it was also credited with a photograph taken at the greatest distance. Peeping out of the arched scaffolds of the Victorian Court, Joseph Turner’s photograph, The Moon, Nine Days Old, was taken at the great Melbourne Telescope on 1 September 1873. That image was widely reproduced and exhibited, first at the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Belfast in 1874, then in Philadelphia in 1876, and again at the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London and the 1887 Dublin Exhibition.14 Turner’s image of the moon would become the most authoritative photograph of its subject for close to two decades. In Philadelphia, it sat amongst views of ploughed land and behind bales of hay and piles of produce as a seminal example of the astronomical photography that would burgeon over the next decade.

-

Bruno Giberti, Designing the Centennial: A History of the 1876 International Exhibition in Philadelphia, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2002, p. 220. ↩

-

International Exhibition 1876 Official Catalogue: Part II, Department IV- Art - Art Gallery, annexes, and outdoor works of art, rev. ed., John Nagle and Company, Philadelphia, 1876, p. 8. ↩

-

Karen Magee, Captain Sweet’s colonial imagination: the ideals of modernity in South Australian views photography 1866–1886, PhD thesis, University of Adelaide, 2015, p. 186. ↩

-

Ken Orchard, ‘J. W. Lindt’s Australian Aboriginals (1873–74)’, History of Photography, vol. 23, no. 3, 1999, p. 167. ↩

-

Richard Bradshaw, Henry Beaufoy Merlin, 1830–1873, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Available at: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/merlin-henry-beaufoy-13096. Accessed 12 September 2019. ↩

-

Australian Town and Country Journal, 27 September 1873, p. 10. ↩

-

Australian Town and Country Journal, 11 January 1873, p. 2. ↩

-

Alan Davies, The Greatest Wonder of the World, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 2013, p. 12. ↩

-

Judy Annear (ed.), Photography: Art Gallery of New South Wales Collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2007, p. 41. ↩

-

Gael Newton, Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1839–1988, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1988, p. 54. ↩

-

Helen Ennis, A Modern Vision: Charles Bayliss, Photographer, 1850–1897, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2008, p. 1. ↩

-

Alan Davies, The Greatest Wonder of the World, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 2013, p. 12. ↩

-

‘The Largest Photograph in the World’, Oakland Tribune, California, 8 June 1876, p. 1. ↩

-

Richard Gillespie, The Great Melbourne Telescope, Museums Victoria, Melbourne, 2011, pp. 104–10. ↩