(Installation View, pp. 191–202)

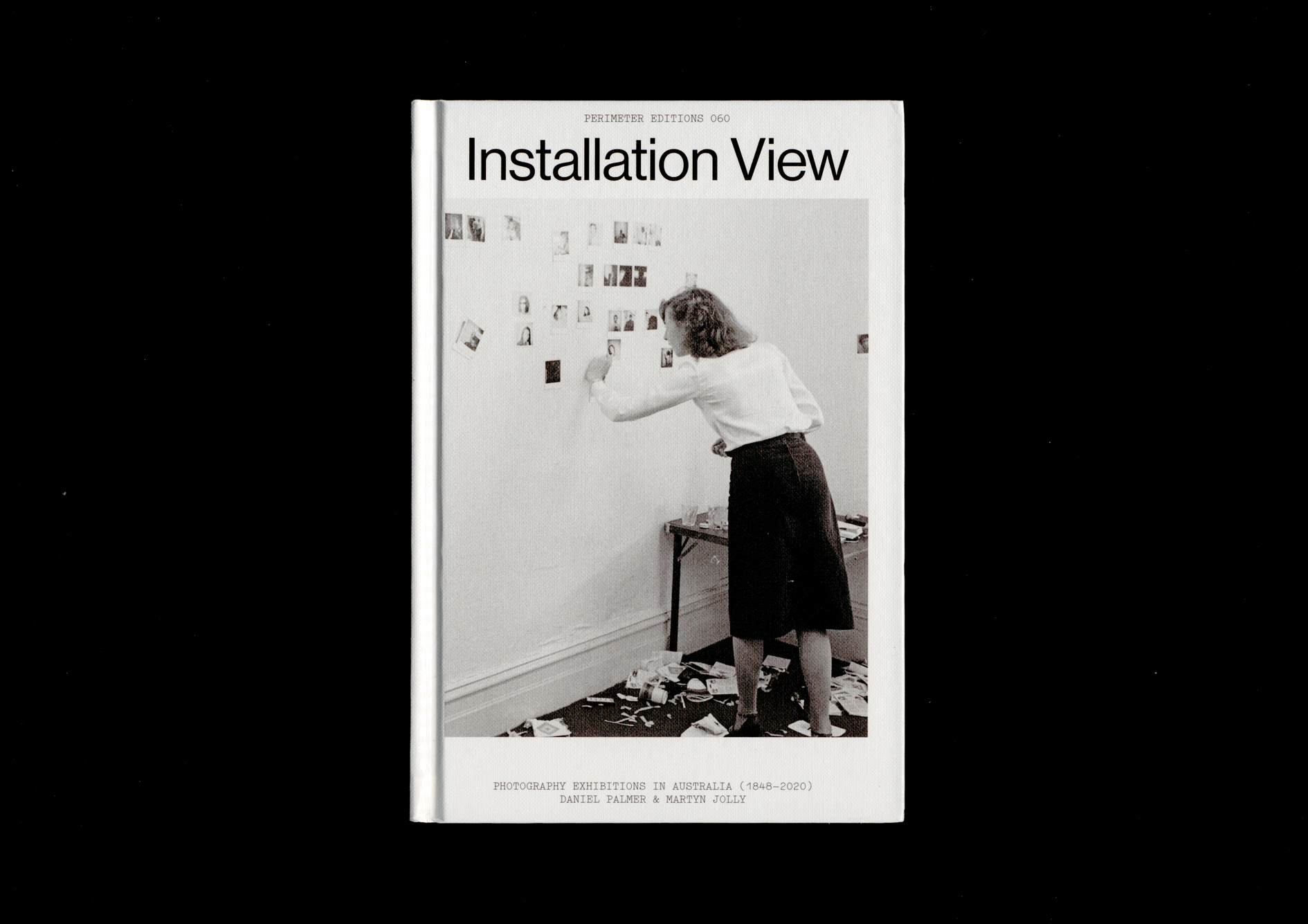

The warm Sydney evening of Thursday 21 November 1974 was a big one for Australian photography. Dressed in a paisley shirt, Margaret Whitlam, one half of Australia’s most glamorous and powerful couple, opened the inaugural exhibition at the Australian Centre for Photography (ACP). Her husband, the Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, had reorganised and radically increased the funding for the Australia Council following his election in 1972, and in September 1973 the Council had granted the eyebrow-raising sum of $25,000 a year to a photographic ‘foundation’.

While, in Melbourne, contemporary photographers were sporadically supported through a disparate range of galleries and colleges, in Sydney the idea of a national ‘foundation’ for photography emerged out of four years of intensive lobbying and planning by a group of established Sydney figures from the realms of photography (David Moore, Laurence Le Guay and Wesley Stacey), art (curator Daniel Thomas), and architecture (Peter Keys). They were spearheaded by one of Australia’s most prominent photographers, Moore, who had worked extensively overseas throughout his career, and had also been included in The Family of Man. His argument for a ‘foundation’ was simply that ‘the people of this country are surrounded by photographic images in all forms, but have little opportunity of evaluating or understanding them’.1

In the lead-up to the opening of the ACP, debate raged about what form and direction this critical creative organisation should take. In the absence of much other photographic infrastructure in Sydney at the time, it was variously suggested that it should solicit, buy, commission, archive, sell, curate, exhibit, explain, publish and tour the work of all kinds of different Australian photographers – all of whom should in turn expect to be connected, supported, encouraged, discovered, remembered, publicised and educated through the new centre. In short, expectations were impossibly high and the ACP attracted controversy even before it opened.2

All of the men (and they were all men) involved in setting up the ACP were acutely aware of overseas models, such as The Photographers’ Gallery in London, established in 1971; the Royal Photographic Society, also in London, founded in 1853; and the International Centre for Photography, founded by Cornell Capa in New York in the same year the ACP opened. As the reality of establishing the institution began to bite, its broad remit focused in on the visual arts. In particular, the centre would use the established tradition of museum-based art photography from the United States to establish Australian photography as a legitimate art form once and for all. The doyen of that ‘tradition’ was John Szarkowski, director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Through his program of catalogues and exhibitions, some of which – such as The Photographer’s Eye, 1966 – had toured to Australia, Szarkowski had established the aesthetic terms supposedly ‘inherent’ to the medium itself through which photographs could be evaluated as art. The Australia Council granted additional funding to bring Szarkowski to Australia to open the new centre in mid-1974, but due to delays the centre was not completed in time, so Szarkowski undertook an influential lecture tour instead.3

Finally, in November, the ACP was ready. Its newly appointed director, Graham Howe – back from a stint at the The Photographers’ Gallery in London – described the evening vividly. Mrs Whitlam, who because of a plane strike had to be driven from Canberra through the heat, arrived in Sydney’s trendy commercial gallery precinct of Paddington at 6pm, when the streets around the gallery lay in ‘low angle, long shadow’ sun, and ‘light textures were very rich and full’.4 The newly restored corner terrace was ‘infested’ with photographers, many of whom crowded onto the small corner balcony to photograph the elongated shadow of the policeman assigned to protect the Prime Minister’s wife on the street below.5 Whitlam had a couple of glasses of champagne and then gave a lively and amusing speech.6

The exhibition was called Aspects of Australian Photography. Endowing the key word of that moment, ‘tradition’ with a capital ‘T’, Graham Howe said he had curated the exhibition ‘to suggest some of the dimensions of Australian photography as it applies to the Tradition’.7 And indeed, each of the six male photographers Howe selected provided a slightly different, though ultimately unsurprising, take on established genres: Grant Mudford used formalist urban compositions ‘to articulate visual ambiguities’;8 John Walsh shot firmly within the gritty post-war documentary tradition; Ian Dodd’s intimate snapshots of women were ‘mysteries of lyrical beauty’;9 Phillip Quirk grabbed visually witty 35 millimetre shots out of everyday Australian life; Ken Middleton referenced pop art, but used the handmade gum-bichromate process ‘in a bawdy multi-coloured montage of freaks and carnivals’;10 and Max Pam made ‘a momentary fix … within the disordered flux of experience’ with his square framed photographs from the hippy trail in Asia.11

In his introduction to the book published to accompany the exhibition (and hoped-for touring show), Patrick McCaughey, professor of visual arts at Monash University (and later director of the National Gallery of Victoria), gave photographers a patronising lecture on ‘The Identity of Photography’.12 Admitting that for him photography was a ‘puzzling art’, he noted the ‘jumpiness and unevenness within nearly every exhibitor and the disparity in quality between them’. This was because they were not following Szarkowski’s dictums closely enough. They were trying to be ‘artists’ rather than embracing the inherent ‘casualness’ of the medium and controlling it through the photographic series.13

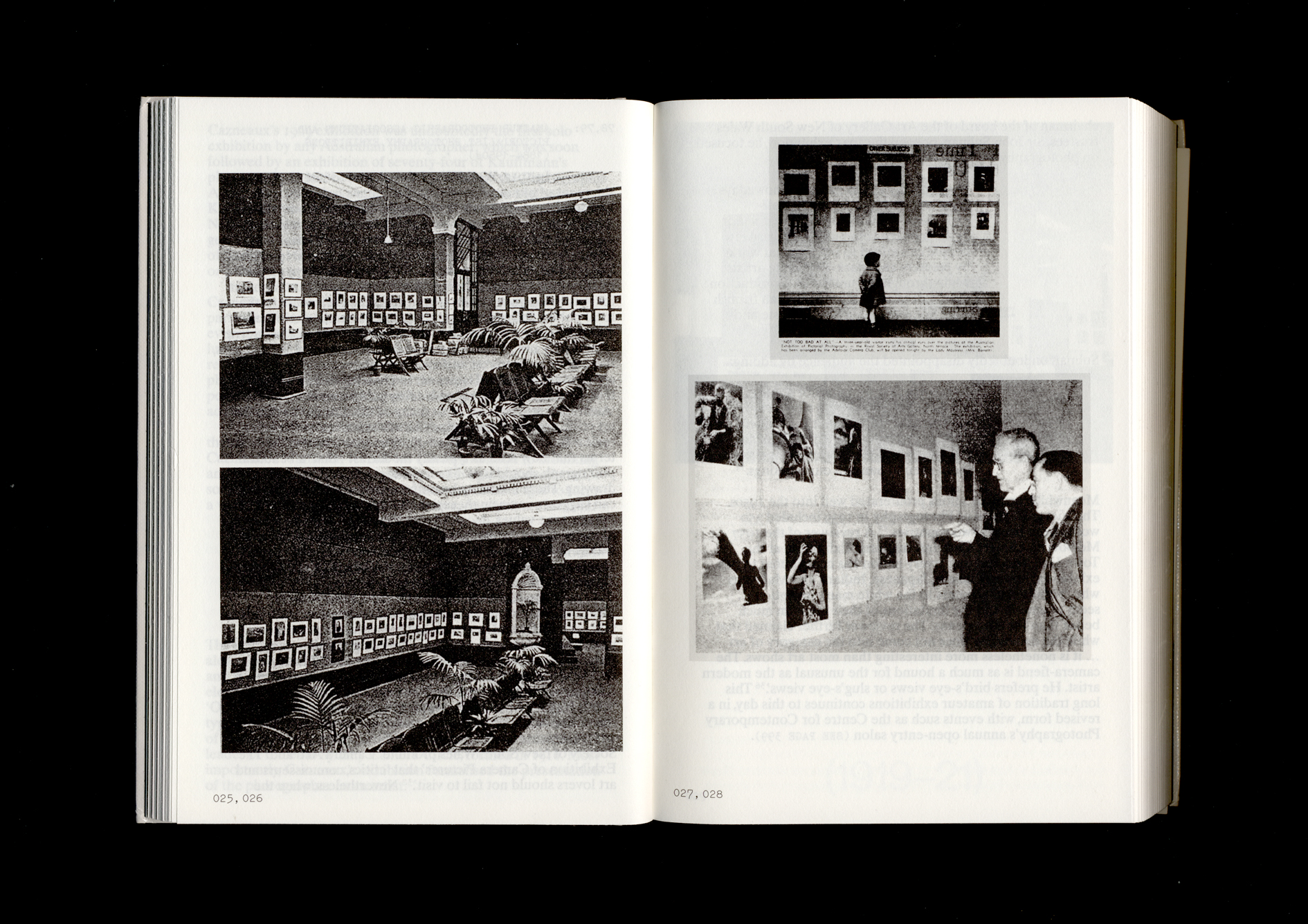

ACP’s refurbished Victorian era Paddington building architecturally embodied this mode of working with the ‘casualness’ of photography through the photographic series. To make a ‘congenial and friendly place where photographers would be pleased to meet and discuss their ideas and exchange opinions’,14 the designer Peter Keys used an unobtrusive brown colour scheme, all the way from the exterior stonework to the new, brown flecked cord carpet. He retained many of the original Victorian features, such as winding stairs to an upper gallery and balcony, but there was no space left for meeting or lecture rooms. Howe knew that photographs ‘aren’t quite so loud speaking as paintings’,15 so money was invested in the aesthetics of the new galleries. They featured inbuilt colour-corrected fluorescent tubes and a modular hanging system. Moore had designed a magnetic system of vinyl covered steel sheeting on the wall, with magnets to hold the frames in rows (described in detail in one newspaper article on the opening show).16 The centre invested in a stock of aluminium frames each with the same square profile, and in standardised dimensions based on the sizes in which packets of photographic paper were purchased – 16 x 20 inches, 20 x 24 inches and so on.

This modular system, which was maintained even after the ACP moved to its new premises on Oxford Street in 1981, tangibly encapsulated – in a distinctively 1970s palette of materials and colours – the ‘tradition’ of photography as modern art, where the image travels seamlessly from reality to camera to enlarger to print, to a series of identically sized frames in a row on a wall, and where one photographer’s personal ‘vision’ can be replaced by the next without disturbing the modular structure of the medium’s tradition as a whole.

-

See Vogue, October 1973, p. 64, quoted in Deborah Ely, ‘The Australian Centre for Photography’, History of Photography vol. 23, no. 2, 1999, p. 119. ↩

-

As Ely, ‘The Australian Centre for Photography’, p. 120, has written: ‘The notion that the centre could cater for and be receptive to everyone making good photographs was clearly impractical and the promise left many photographers feeling disgruntled’. ↩

-

Szarkowski gave six public lectures titled ‘Towards a Photographic Tradition’. The purpose of the national tour, as Howe put it at the time, was to liberate photography from the world of technique and commerce and to suggest that it could also be of absorbing artistic and intellectual interest. See: Graham Howe, ‘The Szarkowski Lecture’s, Art & Australia, July–September, 1974, p. 89, and Michael Fitzgerald, ‘A Great Stir: Revisiting Szarkowski’s 1974 trip to Australia’, Photofile 93, Spring–Summer 2013, pp. 70–3. ↩

-

Graham Howe, interview 28 November 1974, reproduced in Toby Meagher, Developing Photography: A History of the Australian Centre for Photography 1973–2013, Masters in Arts Administration thesis, University of New South Wales, 2013, online at: https://www.photo-web.com.au/papers/meagher. Accessed 12 June 2017. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Graham Howe, letter to Mrs Gough Whitlam, 28 November 1974, Australian Centre for Photography archives, Ultimo, Sydney. ↩

-

Graham Howe, Aspects of Australian Photography, Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, 1974, p. 2. ↩

-

ibid., p. 6. ↩

-

ibid., p. 30. ↩

-

ibid., p. 50. ↩

-

ibid., p. 62. ↩

-

Patrick McCaughey, ‘The Identity of Photography’, in Aspects of Australian Photography, Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, 1974, pp. 3–5. ↩

-

ibid., p. 4. ↩

-

Graham Howe, interview 28 November 1974. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

‘Photo centre in Sydney opened’, The Canberra Times, 4 December 1974, p. 13. ↩