(Installation View, pp. 19–28)

In February 1848, the British-born itinerant daguerreotypist J. W. Newland disembarked in Sydney with almost two hundred daguerreotypes in his baggage. These unique palm sized images, formed on the mirrorlike surface of polished metal plates, included portraits of Pacific Islanders and views of key trading ports he had exposed during the previous three years in Central and South America, the Pacific and New Zealand. When he opened his portrait business on George Street in March that same year, he put them on display as ‘Newland’s Daguerrean Gallery’. It was lavishly praised in the press, and for the first time Australian colonists could directly see the broader antipodean world of which they were a part.

Prior to this, the curious public had only occasionally been able to see individual daguerreotypes on public display. For instance, in February 1847, some of the British-born photographer Robert Hall’s daguerreotypes of Aboriginal subjects were exhibited on a table amongst the 178 drawings, watercolours and paintings in Exhibition of Pictures, the Works of Colonial Artists at the South Australian Legislative Council Chambers.1 But ‘Newland’s Daguerrean Gallery’ was the first solely photographic exhibition in Australia. An important part of the experience of visiting the gallery was not only seeing likenesses of those from far away, who you had only read about or seen in prints and lithographs, but also of seeing likenesses of those you saw almost every day. As contemporary accounts reveal, the gallery became an active site of colonial representation as the local was interpolated into the global:

Amongst the numerous interesting specimens on view, are the miniatures of the renowned [Tahitian] Queen Pomare and family, New Zealanders, Feejeans [sic], and the inhabitants of the South Sea Islands. To these the Messrs. N. are daily adding those of many well-known residents in Sydney, which none can fail to recognise at a glance. The superior artistical finish, of the portraits is an additional recommendation, besides being a guarantee of the fidelity of the likeness in the most minute particular.2

Daguerreotype studios in the mid nineteenth century became not only places where you could go to get your portrait made – perhaps to send to your family back ‘home’ in Britain – but also places where you could see diverse exhibitions of the latest types of image-making, and personally experience the latest technologies from around the world. For instance, in 1855, British-born photographer T. S. Glaister opened a studio in Sydney advertising himself as ‘late of the distinguished firm of Meade Brothers and Co., New York’.3 At the studio in 1856 ‘[h]undreds of portraits of eminent men, and views of public places adorn the walls’, while three-dimensional scenes of Europe could be viewed through a stereoscope.4 Daguerreotype studios were therefore nodes in complex webs of global connection and, in that respect, they served a related function to the large international exhibitions of the period.

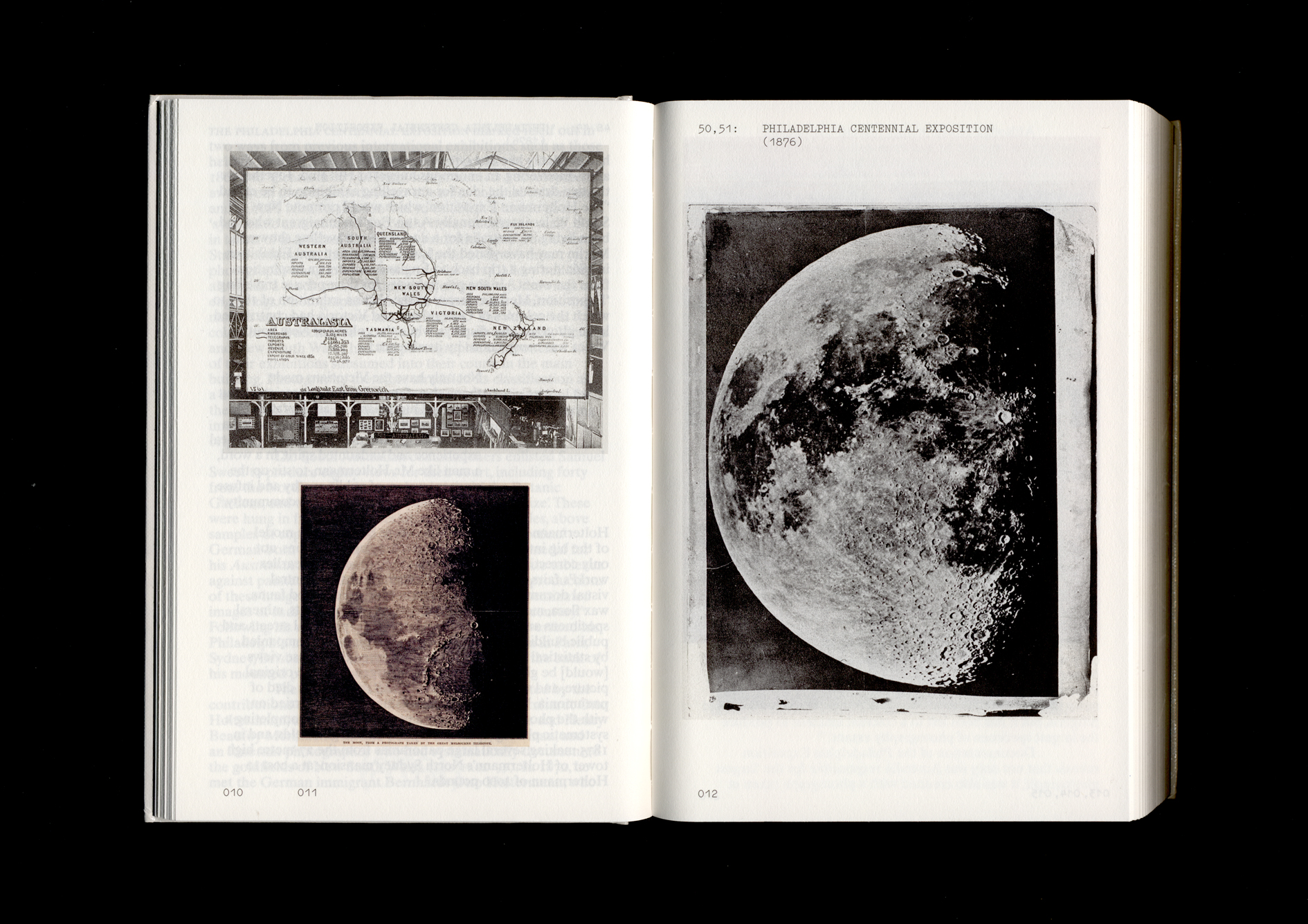

In 1854, the colonies of both New South Wales and Victoria began planning exhibits for the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris, showing them in Sydney and Melbourne first. Melbourne built a new building for its exhibition, 5 and New South Wales used the not-quite-completed Australian Museum on the corner of William and College Streets. Thousands of Sydneysiders paid a shilling to see the specimens of wood, examples of handicrafts, models of machinery, and a collection of photographic portraits, views and stereographs by which Paris would soon come to know Sydney. One visitor, patriotically signing himself ‘An Australian’ hopefully imagined that: ‘The [daguerreotype] view of George Street by [James] Gow will give the French an idea of the magnificent buildings of Sydney.’6 Subsequently, before the exhibition was packed up for Paris, James Gow took a daguerreotype view of its interior, a rare practice at the time. In the lithograph F. C. Terry made from Gow’s daguerreotype, viewers can be seen moving with metropolitan ease among the various exhibits.

By the late 1850s, Sydney, with its economy booming, had become a crowded and competitive marketplace for photographers. Customers with an appetite for novelty eagerly adopted new developments in the medium, including new photographic cameras, such as the stereoscope, new photographic lenses, new emulsions, including collodion and albumen, new substrates, including glass, metal and waxed paper, and new treatments such as enamelling and hand-colouring. Newland had left Australia in 1848 after a stint in Hobart, but Sydney now had several photographic studios, including three large ones – Edwin Dalton, Glaister and Freeman Brothers – all of which sold equipment and exhibited photographs in addition to making portraits, and occasionally views.

Sydney’s two big opticians, the Flavelle Brothers and Brush & MacDonnell, also displayed photographs, particularly stereographs, in order to sell what were at the time still called ‘philosophical instruments’ (various optical devices such as microscopes marketed for the ‘rational entertainment’ of examining natural phenomena). Sydney’s music and print publishers also began to play an important role for local photography by plugging into global networks of commercial image circulation. For instance, in mid 1856 Woolcott and Clarke imported from the London print publisher Joseph Hogarth a collection of more than two hundred salt paper photographs, printed in London from either waxed paper or collodion glass negatives. They charged colonists a shilling to feel connected to trends and events overseas. The Empire commented:

In England … exhibitions of photographs are quite the rage, and after inspecting [these] specimens … Here, in George Street, Sydney, we may gaze on the architectural beauty of Windsor Castle, or Canterbury Cathedral, with perfect assurance that no cunning artist hand has exaggerated their beauties or concealed their defects … The more they are dwelt upon the more marvellous they appear, nay, by applying powerful magnifying lenses, fresh beauties constantly present themselves to the spectator.7

But there was not only European beauty on display – there was also European news. The Crimean War had only just ended a few months before, and for the first time – in about fifty photographs taken by Roger Fenton, James Robertson, Frank Haes and others – Sydneysiders could see the hills of Balaklava and the destroyed docks of fallen Sebastopol, and witness the ‘stern realities of a soldier’s life’.8

The effect of the complete exhibition on Sydney was profound. For audiences it awakened ‘deep and hallowed associations … [t]here is hardly a light or shadow in the whole which does not suggest a train of thought fraught with the most important reminiscences, both as regards the natural decay of human works and the mortality of human nature’.9 For Sydney’s growing number of amateur photographers, the exhibition must have also provided an important context. Amateurs such as William Stanley Jevons or Matthew Fortescue Moresby met regularly to view each other’s work at the Philosophical Society of New South Wales. The British photographer Frank Haes, whose images had been exhibited at the Woolcott and Clarke exhibition, visited Sydney himself the following year, bringing with him one of the new, faster Petzval portrait lenses and some experimental dry plates for the Freeman Brothers. In Sydney, he made photographs and read a technical paper to the Philosophical Society on the waxed paper process. Back in Britain, he reported on the state of Australian photography:

At the present time every new process is tried as soon as we hear of it, except the albumen on glass, because the Colonies in general suffer much from dust-storms which find their way into every nook and cranny … In Sydney there are about thirty amateurs and twenty-five professional photographers, besides many who are always travelling in the interior from town to town … I do not think that photography has reached the same degree of excellence in Melbourne as it has in Sydney; the former being a busier place, does not number so many amateurs.10

Melbourne was in the grip of gold fever, while in Sydney the interaction between entrepreneurial professionals, eager clients, philosophical instrument stores, stationers and print publishers (all with direct connections to British and European exporters) and sophisticated and educated amateurs working at places such as the Sydney Mint and Sydney University created a richer photographic environment.

For instance, at his Excelsior Photographic Galleries in Pitt Street, Glaister exhibited collodiotypes (collodion emulsion positives on glass) up to a size of forty-three by fifty-eight centimetres. This was something for the colony to be proud of:

We have received assurances, from artists of repute at home, that the London photographers are quite eclipsed by our Sydney practitioners. By them the superiority of photographs done here (we allude only to collodiotypes) is ascribed to the influence of the climate, and it is reasonable to oppose that the superior intensity of the sun’s rays should have given us advantage over those taken beneath the sickly sun that has to force its way through a murky London atmosphere. At all events Messrs. Dalton, Freeman, or Glaister have nothing to fear by comparison with any English photographic artists. We hope to see a Photographic Exhibition in Sydney before long. It would be very attractive.11

The regular monthly meeting of the Philosophical Society of 8 December 1858 had become a special ‘Photographic Conversazione’. Members were asked to contribute specimens of photography and even ‘invited to bring with them on this occasion the ladies of their family’.12 James Freeman from Freeman Bothers read a well-informed paper, ‘On the Progress of Photography and its Application to the Arts and Sciences’, and showed specimens of his studio’s work. The painter and photographer Edwin Dalton displayed his ‘Photo-crayotypes’ (a photographic print coloured in pastel) which he then put on public display at his own Royal Photographic Rooms.13 Haes, who had returned to Sydney in late 1858 after exhibiting seven salt print photographs from wax paper photographs of Australian subjects in the London Photographic Society’s exhibition at the South Kensington Museum, also exhibited 300 photographs.

A year later, on the evening of Monday 19 December 1859, an even larger Photographic Conversazione was held at the hall of the Australian Library:

An invitation was sent to the professional and amateur photographers of Sydney, and also to the possessors of valuable works by continental artists, to exhibit some of their pictures, and the result was a very extensive and entertaining collection of the choicest productions of the photographic art.14

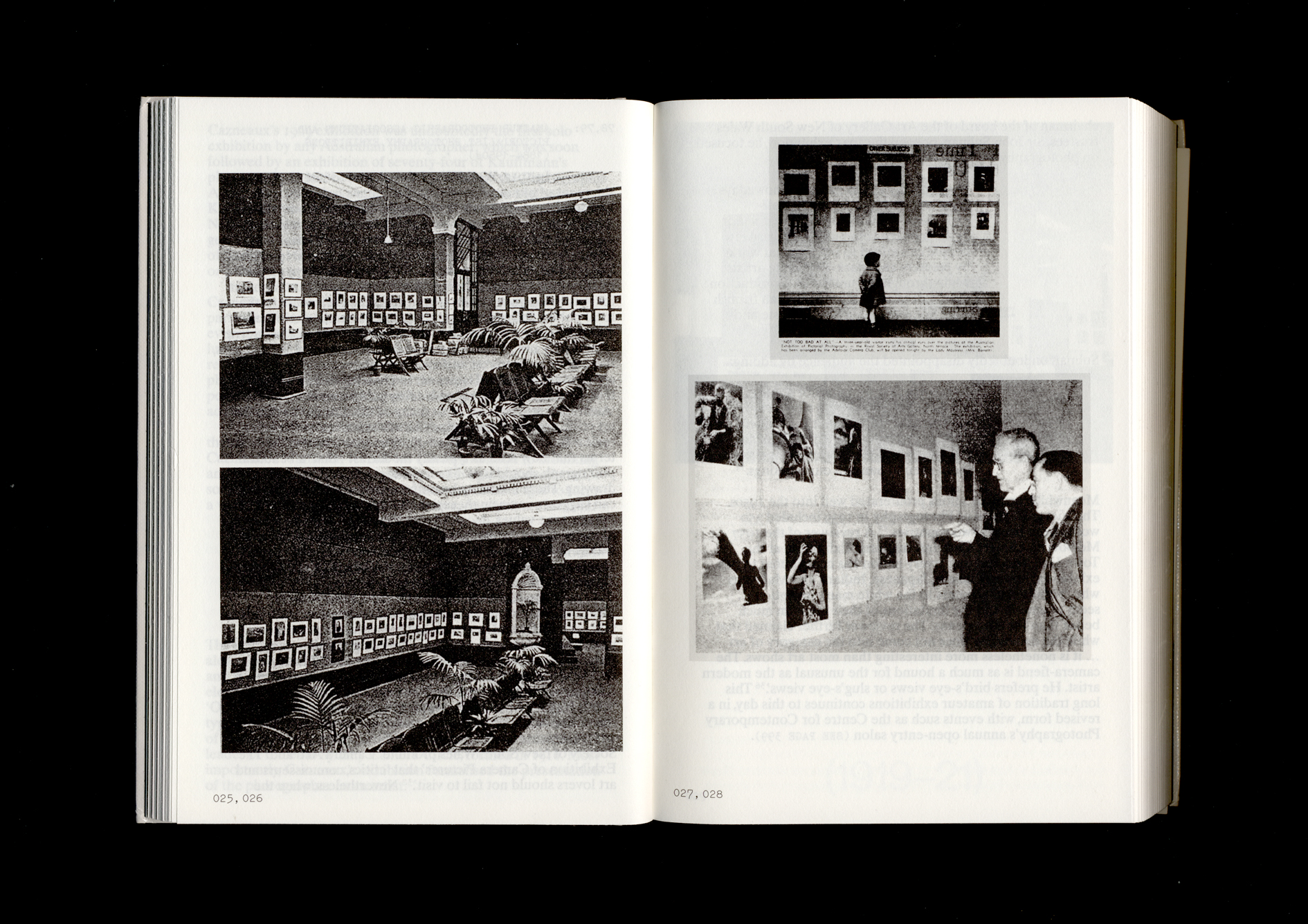

The exhibition included hundreds of photographs from Britain, Europe and the Middle East imported by wealthy enthusiasts, and hundreds more photographs made in Sydney by professionals and amateurs. They included a wide variety of portraits, views and stereographs on glass and paper, painted and unpainted, in albums and in frames. The latest specimens from overseas were there, including three of French photographer Gustave Le Gray’s apparently ‘instantaneous’ large-scale marine studies of only a few years before and twelve microscopic photographs complete with three compound microscopes with which to view them. Although Glaister submitted no pictures, the achievements of other colonial professionals were there: William Hetzer’s neatly packaged stereographs of Sydney and its environs, a daguerreotype panorama of Sydney Harbour by the Freeman Brothers, and fourteen views taken by them from a platform erected around the large plinth a statue in the Domain. The enormous output, particularly in stereography, of Sydney’s amateurs such as Professor John Smith, Robert Hunt and Joseph Docker was also on display. The dazzling night was the culmination of a decade of intense photographic interaction both within Sydney, and between Sydney and the rest of the world.

-

South Australian Register, 13 February 1847, p. 2. Isobel Crombie notes that, ‘The earliest known daguerreotypes of Aboriginal subjects were taken by Robert Hall in South Australia around 1846 and were listed in A Catalogue of the Exhibition of Pictures, the Works of Colonial Artists’ as ‘S.A Native, Daguerotype [sic]’, ‘Four Aborigines, Daguerotype [sic]’, and ‘S.A. Native, Daguerotype [sic]’. These are not extant. Crombie also notes that four of Douglas Kilburn’s daguerreotypes of Victorian Aboriginals were included in the Art-Treasures Exhibition in Hobart in 1858, which included photographs from France and Britain as well as local photographers such as Fred Frith and M.P Dowling. See Isobel Crombie, ‘Australia Felix: Douglas T. Kilburn’s Daguerreotype of Victorian Aborigines, 1847’, Art Bulletin, vol. 32, 1991, pp. 21–31. ↩

-

‘The Daguerrean Gallery’, Bells Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 11 March 1848, p. 2. ↩

-

‘Daguerreotype Portraits’, Bells Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 21 April 1855, p. 3. ↩

-

The People’s Advocate and New South Wales Vindicator, 5 January 1856, p. 3. ↩

-

The Melbourne Exhibition included daguerreotypes by Douglas T. Kilburn and ‘collodiotypes’ by Walter B. Woodbury. ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 December 1854, p. 8. ↩

-

Empire, Sydney, 24 May 1856, p. 4. ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 May 1856, p. 4; The People’s Advocate and New South Wales Vindicator, 24 May 1856, p. 4. ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 May 1856, p. 5. ↩

-

The Journal of the Photographic Society, London, 22 March 1858, p. 179. ↩

-

The Sydney Magazine of Science and Art, 2, 1859, p. 156. ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 December 1858, p. 1. ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 February 1859, p. 8. ↩

-

The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 December 1859, p. 5. ↩