(Installation View, pp. 245–260)

Established in 1982, Art and Working Life was the title of a program and a $140,000 incentive fund developed by the Australia Council and the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), designed to encourage art practice informed by the concerns and issues affecting workers’ lives and acknowledging working class cultural traditions. Running over four years until 1986, the activities associated with the program sum up the left-wing politics of art photography in this period, when so many issues of the day – feminism, uranium mining, Aboriginal land rights – were refracted through a Marxist class analysis of capitalism, which often ended up focusing on the boss and the worker, the industry and the union.

Art and Working Life was a product of a time when about half the Australian workforce was still a member of a trade union. Indeed, in 1983, the former president of the ACTU, Bob Hawke, was elected as Prime Minister in a landslide election and enjoyed an unsurpassed approval rating in November 1984 of seventy-five per cent. As a realist medium which lent itself to graphic reproduction in combination with text, photography was at the centre of this program (perhaps followed by community theatre). Whilst attempting to bring together ‘art’ and ‘working life’, the program also revealed significant differences and tensions in the role of photographers and photographic exhibitions at the time.

Typical Art and Working Life photography projects include And so…we joined the union, 1985, by Ruth Maddison, Carolyn Lewens and Wendy Rew, commissioned by the Victorian Trades Hall Council Information and Resource Centre to document women at work and as active committed unionists.1 The artist Helen Grace had taken the photographs for a TAFE poster campaign, Girls Can Do Anything – designed to encourage young women to take up apprenticeships – which was exhibited on Sydney buses and trains in Sydney 1981–86. In 1984, as part of Art and Working Life, Grace presented Re-presenting Work in collaboration with Julie Donaldson, the work safety expert Warwick Pearse, and the artist Ruth Waller, at the Workers’ Health Centre, Lidcombe. Directed towards occupational health and safety issues, their aim was to raise questions about the uses of photography in the workplace, when a major part of workers’ lives – their workplace – was not documented by them or for them, but rather was limited to management’s public relations.2 Eleven workplaces were visited through their unions, from the paint industry and the print industry to the manufacturing industry, and contact sheets were shared with workers. Waller, a painter, laid out five poster-sized panels with cut-out blocks of typography, graphically embellished with bars of yellow and red reminiscent of Soviet Novyi Lef (New Left) posters (a style which was also being appropriated by British pop magazine The Face and the New York conceptual artist Barbara Kruger). The panels were then laminated in plastic with holes punched in each corner for ease of transportation and installation. After an exhibition at the Lidcombe Workers Health Centre, the panels toured community and union venues in 1984.

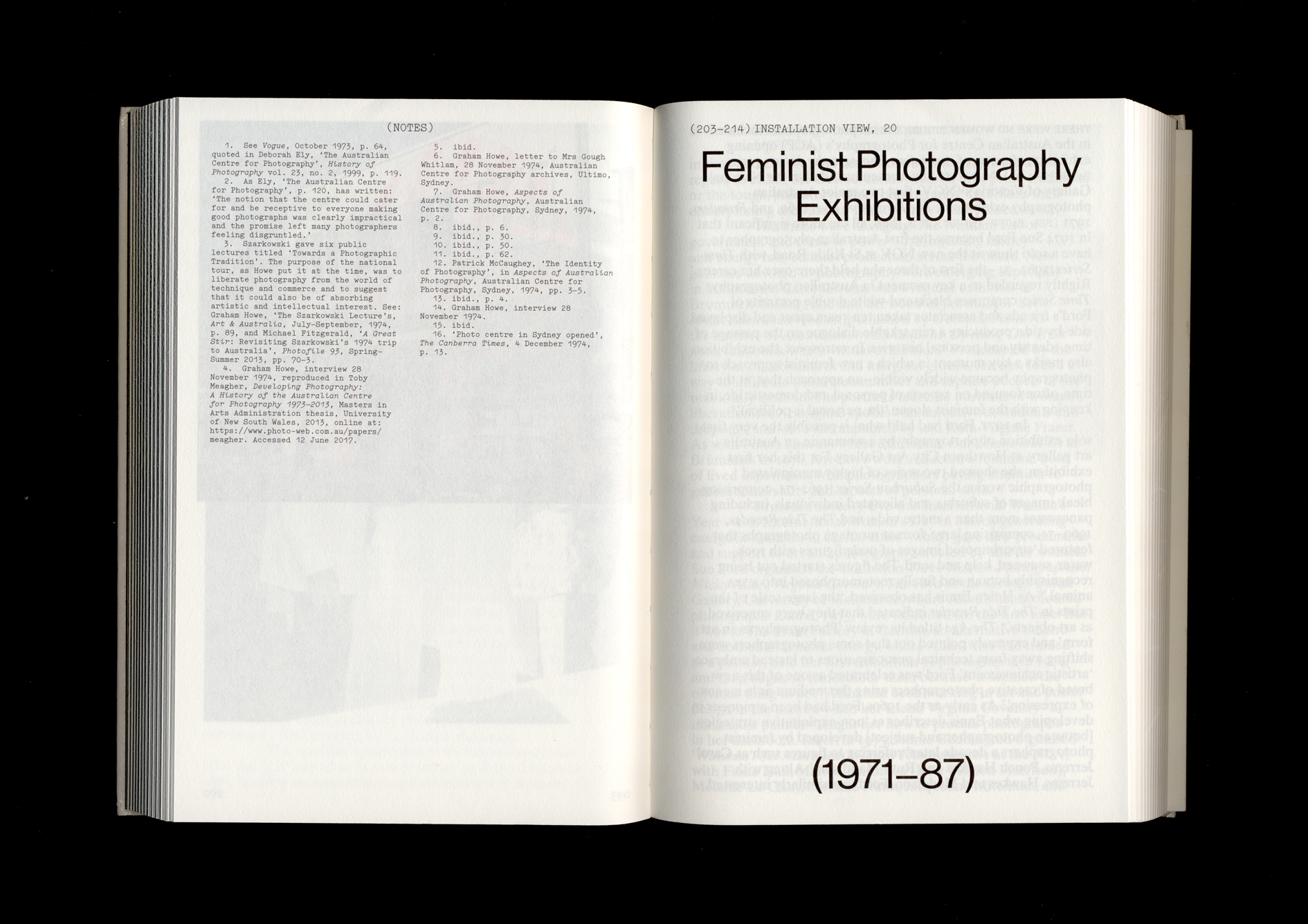

Projects such as these revealed several historical influences. Within Australia, the long tradition of colourful union banners produced for marches and rallies was an important inspiration. Within photography, the community darkrooms and the political photography movements in the UK during the 1970s were also very influential. These included the Half Moon Photography Gallery and its breakaway Photography Workshop, the Cambridge Darkroom, and the Hackney Flashers Collective, of which Helen Grace had been a member. Their publications, whose writers had links to British polytechnics and universities, were widely read in Australian art schools and universities. Camerawork and Ten.8 magazine, and the books Photography/Politics: One3 and Photography/Politics: Two,4 discussed contemporary photographic and political theory and practice, as well as historical research into worker and anti-Fascist photography of Weimar Germany, the early Soviet Union, and the pre-war US and UK. In 1980, the Melbourne journal Working Papers on Photography (WOPOP), edited by photographers Euan McGillivray and Matthew Nickson, organised Australia’s second Australian Photography Conference at Prahran College of Advanced Education (the first having been organised in Sydney by Wayne Hooper of the University of Sydney’s Department of Adult Education in 1977).5 Amongst a wide range of practical and historical presentations was a report from the cultural historian Anne-Marie Willis on her Australian Gallery Directors Council funded research into nineteenth century Australian photography, and a major paper ‘Mods and Docos’ by Helen Grace, Charles Merewether, Toni Schofield and Terry Smith. There were two major international papers: ‘The Traffic in Photographs’ by the American theorist and photographer Allan Sekula, and an exhibition and paper by the British art historian Kenneth Coutts-Smith on Klaus Staeck, a German poster artist in the style of John Heartfield.

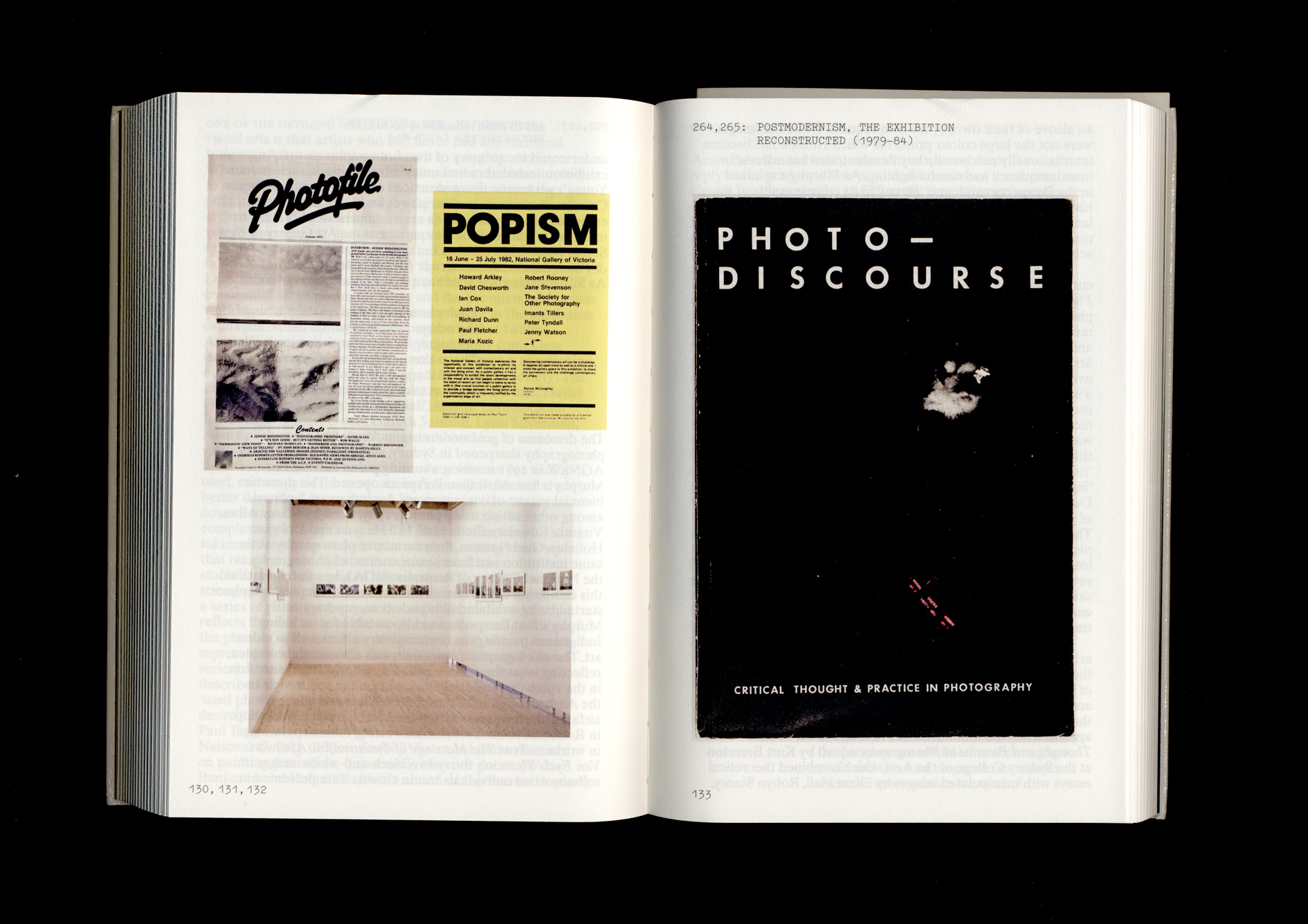

The community darkroom model had an impact on Tamara Winikoff, director of the Australian Centre for Photography (ACP) from 1981 to 1985, who tried to break from the American fine print tradition to broaden and connect the ACP to a wider variety of local communities. The ACP began to publish a tabloid format magazine Photofile; lectures, talks and forums became more regular; the smaller gallery became ‘Viewpoints’, which was devoted to young and emerging photographers selected by a curatorium; the workshop became more sophisticated and elaborate in the courses it offered; and the gallery developed touring ‘suitcase shows’ of laminated panels. Other community darkrooms emerged in Australia, most notably PhotoAccess in Canberra, which thrives to this day.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s photographs with a ‘political’ purpose, such as Art and Working Life, were often graphically laid out on large panels. The style of graphic deployment had influences from two directions: the busy informatic layouts of didactic educational displays, seen in projects such as Re-Presenting Work, and the neutral visual grids of conceptual art. In 1976, for instance, Jon Rhodes had dry-mounted neat text blocks along with his careful black and-white photographs, ordered into elegant temporal sequences and sophisticated formal grids on seventeen panoramic acid-free rag board panels, to narrate the effects of Nabalco mining operations on the Yolngu people of north-eastern Arnhem Land. Titled Just another sunrise? The impact of bauxite mining on an Aboriginal community, the exhibition was shown at the ACP with an introductory panel featuring Nabalco’s rising sun logo (giving the exhibition its title) and a room brochure ‘A Brief History of Yirrkala’.

Virginia Coventry worked in a similar mode for her 1979 work Here and There: Concerning the Nuclear Power Industry, first exhibited at the George Paton Gallery. Her eight panoramic panels on the nuclear industry in Europe and Australia combined neat blocks of typesetting with panoramas and photographs from various sources. Coventry said: ‘I wanted to use the photographs taken by many people to signify, through a collective witness, that we are already experiencing the consequences of living in a nuclear society’.6 These three components were annotated with lace-like lines of agitated handwritten script, as Coventry said: ‘I drew the words’.7 The work is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), which acquired, along with the eight panels, the modest wooden table on which fresh photocopies from contemporaneous newspapers were meant to be placed whenever it was re-exhibited.

The sequencing, ordering and graphic structuring of photographs integrated with text was a very important strategy for photographers to adopt during a period when the individual ‘fine art’ photograph was under deep suspicion. In the theory of the time, the spatial or temporal structuring of multiple photographs inserted a ‘critical distance’ between the viewer and photography’s conventions, whereas the single photograph was most often regarded as either an unproblematic ‘window’ on the world, or an unproblematic ‘mirror’ for the photographer’s own subjectivity.8 Coventry curated an exhibition at Sydney’s new Artspace in 1983 around this idea (The Critical Distance), which included Sandy Edwards’s A Narrative With Sexual Overtones, 1983, produced during her involvement with the Blatant Image Collective. But for photographers, this structuring also had to bridge the gap between photography as activism and photography as aesthetics, and between their role in non-institutional community spaces of communication as well as conventional art spaces for contemplation.

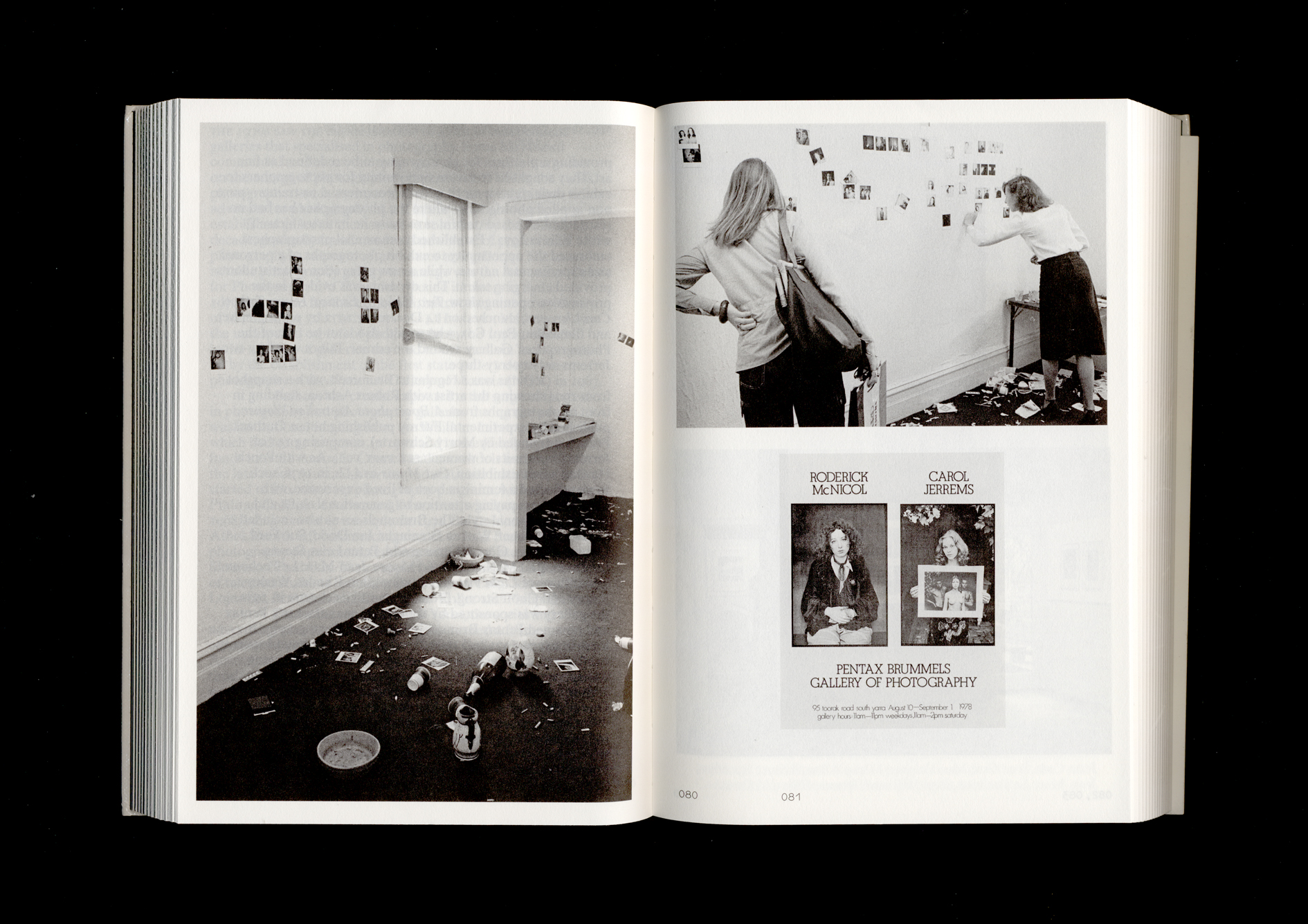

Moving between community and gallery spaces was part of the self-identity of many politically and professionally committed photographers with sophisticated practices, such as Helen Grace, Ponch Hawkes and Ruth Maddison. A notable example of a large project that crossed back and forth between community and gallery during this period was Vivienne Binns’ community arts project Mothers’ Memories Others’ Memories, 1979–81, in which participants recounted autobiographical and biographical narratives about women in their families using photographs, postcards and captions, ‘amongst a treasure trove of handiwork and other domestic memorabilia’.9 The project took place in the community, and was exhibited at community venues, but parts of it were also exhibited at the George Paton Gallery and at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) as part of the the first Perspecta in 1981. Even for sophisticated media artists, the community was a powerful force. Dennis Del Favero’s elaborate and immersive 1984 installation, Quegli ultimi momenti (Those final moments) at the ACP featured an upside-down room, slide projections, a sound environment and photographic panels. To create the sense of loss experienced by migrants caught up in global diasporas Del Favero drew on the Italian Federation of Migrant Workers and their Families (FILEF), a left-wing political and educational organisation with ties to the Labor Party and the union movement, which also published a newspaper, hosted community radio programs and organised conferences, surveys, strikes and petitions.

Corporations also began to appreciate the prestige and energy of young photographers. The photographic manufacturers Polaroid and Kodak both sponsored art projects in the 1980s. From 1973, the cigarette manufacturer Philip Morris had funded the purchase of contemporary Australian art selected by James Mollison, the director of the NGA at the time. Mollison, seeking out the ‘bold and innovative’, flooded what was, for the time, an enormous amount of financial support into the fledgling photographic system.10 Philip Morris, sometimes with the support of the Visual Art Board of the Australia Council’s Regional Development Program, toured exhibitions of Australian photography to the regions. In 1979, as a complementary exhibition to the third Biennale of Sydney, European Dialogues, an outdoor exhibition including Bill Henson photographs of a partially nude boy from 1977, was mounted under the trees of Hyde Park. When it was eventually absorbed by the NGA in 1982, the collection numbered 876 photographs by more than a hundred photographers.

At the same time as the Australia Council was supporting the union movement, it was also promoting the benefits of contemporary art and photography to corporations. In 1978, the major company CSR decided to celebrate the centenary of their Piermont sugar refinery with a big painting of the factory. They approached the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council for the name of a suitable painter. ‘How much do you want to spend?’ asked the Project Officer Michael Goss. ‘$12,000’, they replied. ‘Why don’t you have photography instead of a painting, do something a bit different’, Goss suggested. He called in Christine Godden, the Director of the ACP to ask, ‘which photographer?’ ‘For $12,000 why not select a number of photographers’, she replied.11 Of the six chosen, Jon Rhodes, Sandy Edwards and Micky Allan all used sequences, grids, text and camera-shake – techniques also used in the union sponsored projects – to reproduce the industrial cacophony and repetition of the production line (while Graham McCarter, Mark Johnson and Lewis Morley adopted more traditional approaches). According to Godden, the employees at the Pyrmont Refinery, a number of whom were to be seen in the photographs, made comments ranging from delight to disgust, while the project generated a ‘lively debate … among artists and critics as to the nature and motives of commissioned work’.12 The business world recognised CSR’s courage in opening their factory ‘warts and all’ to scrutiny by the artists, and CSR’s collaboration with the ACP continued until 1986. A further eighteen photographers were commissioned before it was finally gifted to the Art Gallery of New South Wales as a bicentennial gift in 1988.

For decades, modern Australian photographers like Harold Cazneaux, Max Dupain, Wolfgang Sievers and David Moore had built their art careers around muscular corporate commissions for annual reports and advertising. Since the days of Cazneaux’s work for BHP in 1934, many of their industrial commissions had ended up in art collections. But working with art curators to commission works of self-expression by art photographers who were both male and female, young and old, was a new approach for companies such as CSR. However, as Martyn Jolly, co-author of this book, commented at the time in a final catalogue:

Within this particular context [of a corporate collection] each photograph must speak, by definition, from within the corporation’s own definition of itself. Thus, even if some less than rosy images are admitted, they are still seen to be testament to the company’s cultural generosity, as well as its essential honesty and self confidence in submitting itself to outside scrutiny.13

In 1986, the Parliament House Construction Authority commissioned twenty-eight photographers to document the construction of the new Parliament House. Most photographers responded formalistically to the angles and tones of the mud, concrete, and steel reinforcing mesh. But Grace Cochrane also produced nine large collaged panels intended to be hung side by side to form a giant panorama of the building, below which was a layer of portraits of the workers, under which was a collage of newspaper reports on the building and other texts from the history of the site. Sandy Edwards stood out from the rest of the work with saturated colour photographs of workers not ‘on the job’, but rather those involved in the controversial de-registering of the Builders Labourers Federation. Beneath the images, she placed labels filled with her own firsthand experiences of the temporary relationships she forged with the unionists, reflecting an acute awareness of the politics of the commission itself.

-

Catriona Moore, Indecent Exposures: Twenty Years of Feminist Photography, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1994, p. 35. ↩

-

Art & Working Life – Cultural Activities in the Australian Trade Union Movement 1983, exhibition catalogue, Australian Council of Trade Unions and Community Arts Board of the Australia Council, Melbourne, 1983, p. 17. ↩

-

Terry Denton and Jo Spence (eds.), Photography/Politics: One, Photography Workshop, London, 1979. ↩

-

Patricia Holland, Jo Spence and Simon Watney (eds.), Photography/Politics: Two, Photography Workshop, London, 1986. ↩

-

For more on WOPOP, see: Catherine de Lorenzo, ‘Agency and Authorship in Australian Photo Histories’, in Tanya Sheehan (ed.), Photography, History, Difference, Dartmouth College Press, Hanover, 2015, pp. 172–94. ↩

-

Virginia Coventry, ‘Here and There: Concerning the Nuclear Power Industry’, in Virginia Coventry (ed.), The Critical Distance: Work with Photography/Politics/Writing, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney 1986, p. 47. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Mirrors and Windows was the name of a 1978 John Szarkowski exhibition and book at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. ↩

-

Catriona Moore, Indecent Exposures: Twenty Years of Australian Feminist Photography, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1991, p. 44. ↩

-

James Mollison, introduction to Australian Photographers: The Philip Morris Collection, Philip Morris, Melbourne, 1979, p. 4. ↩

-

Robert McFarlane, ‘The Project in Review’, CSR Photography Project Collection: A Bicentennial Gift to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1988. ↩

-

Christine Godden, ‘The CSR Photography Project’, CSR Photography Project: Selected Works, CSR Limited, Sydney, 1985. ↩

-

Martyn Jolly, ‘The CSR Collection’, CSR Photography Project: Selected Works, CSR Limited, Sydney, 1985. ↩