(Installation View, pp. 129–140)

In 1959, The Family of Man exhibition toured from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York to Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane and Adelaide. Originally organised by MoMA’s director of photography Edward Steichen in 1955, where it broke attendance records, the blockbuster exhibition comprised 503 black and white documentary photographs taken in sixty-eight countries, ‘chosen from two million sent in by cameramen all over the world’.1 In reality most of the photographs came from the Life magazine archive, but among the 273 photographers included were two Australian documentary photographers: David Moore and Laurence Le Guay.

By 1959, The Family of Man was halfway through its comprehensive international tour organised by the US Information Agency, during which five copies of the exhibition panels travelled to thirty-eight countries.2 In his introductory essay, Steichen famously stated his belief that photography could offer a ‘mirror of the essential oneness of mankind throughout the world’.3 The exhibition struck a chord with its hopeful post-war message of peace and its comforting metaphor of family – an antidote to the new threat of nuclear annihilation. The Family of Man remains unique among photography exhibitions for the number of critical and celebratory essays and books devoted to its vision of universal humanity.4 Influential denunciations – notably Roland Barthes’ highly critical review of the Paris show in 1956, attacking its sentimental veneer of universality, stereotypical imagery and denial of history – only seem to have enhanced its influence. It is no exaggeration to say that The Family of Man is the most famous exhibition of photography ever staged, a position cemented by a massively successful catalogue that remained in print for decades.

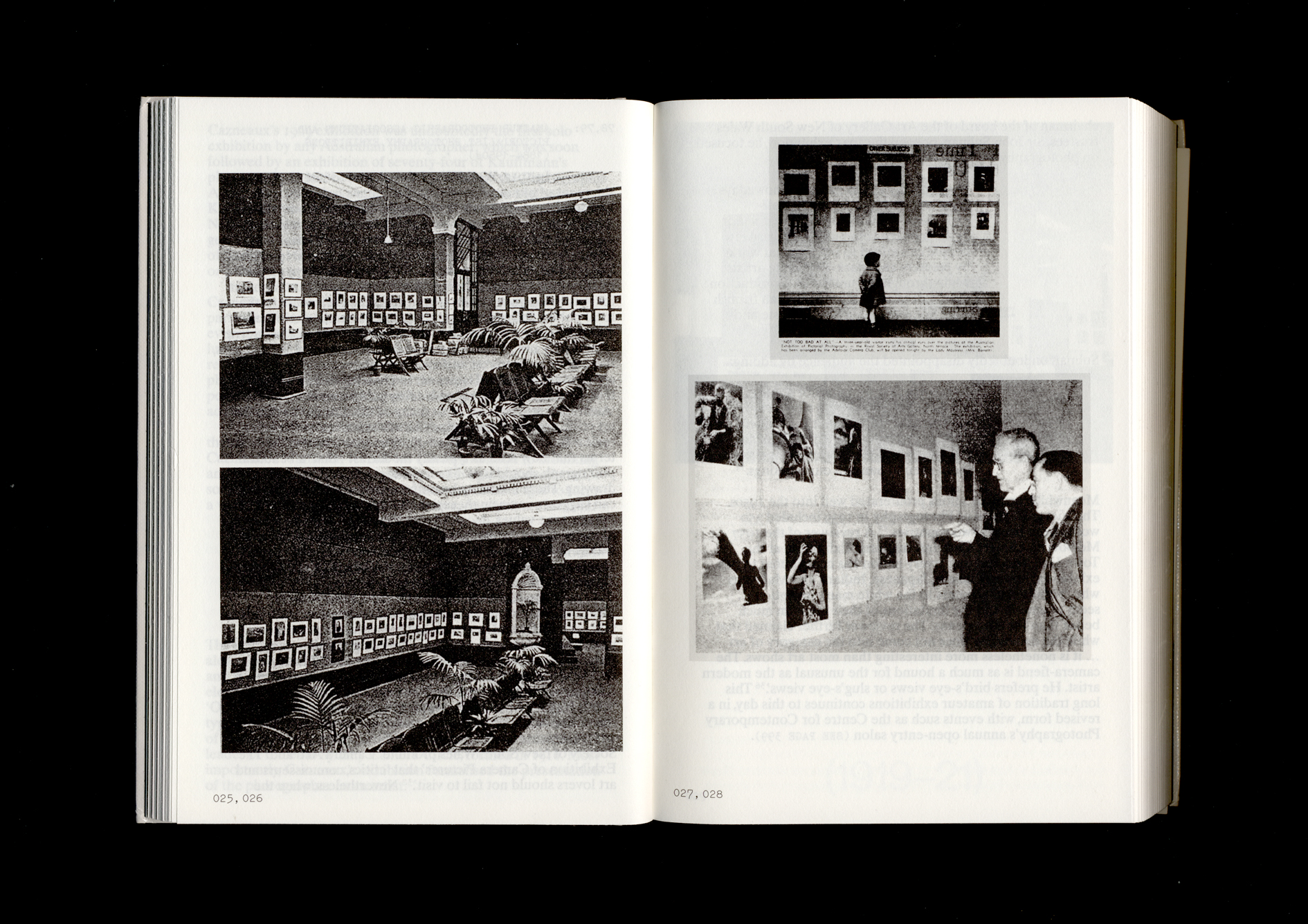

The Family of Man opened in Melbourne in February 1959 at an incongruous venue: the Preston Motors Showroom on Russell Street, which adjoined a church.5 The showroom, since demolished, was an elegant art deco building originally built as a hat factory, but it nevertheless meant that the photographs of war, famine and childbirth were display among another great American export: shiny new motorcars. The photojournalist Wayne Miller, who was Steichen’s assistant on the exhibition, accompanied it to Melbourne and documented its installation and local reception. According to newspaper reports, daily crowds of more than three thousand attendees thronged to visit over its four-week run, even with an admission charge of two shillings sixpence. The exhibition was open daily until 10pm, with the long weekend of the new Moomba Festival (1955–) especially popular. Part of the exhibition’s popularity was owing to its bold and innovative mode of display – designed by US architect Paul Rudolph – in which enlarged, unframed prints of various sizes were presented magazine-style on exhibition panels in small picture groupings. The panels extended into the viewers’ space and created a landscape for them to explore across forty thematic sections – such as love, play, work and death – which incorporated quotes from religious texts and the charter of the United Nations, affirming the commonality of human life. The prints were mounted directly on panels, some of which were free-standing, hanging from the ceiling or against a circular curtain. Local newspaper articles remarked at the scale of the photographs (‘some of them 10 feet high and 12 feet wide’) and their arrival by ship in twenty-nine crates.6

Elsewhere on its Australia tour, The Family of Man was also shown in retail venues. After all, Australia was in the grip of a consumer boom in the 1950s. In Sydney, the exhibition was shown over the entire fifth floor of the David Jones department store on the corner of Elizabeth and Market Street. In Brisbane, it was shown at the John Hicks furniture showroom, and in Adelaide at the Myer Emporium. In Sydney, a newspaper photographer captured a young David Moore and his wife looking at his own photograph, which was included in the exhibition. The image, Redfern interior, was taken ten years earlier in 1949 – an iconic flash-lit image of a young mother and child in a squalid bedroom in an Australian slum.

The photographs were positioned beneath quotes from the Bible. Such family-oriented values help explain why in Melbourne, as Miller’s documentation shots of the exhibition held in the MoMA archives reveal, the exhibition display included a sign with a local appeal from the Citizen’s Welfare Service of Australia: ‘HELP “THE FAMILY OF MAN” AND THE STRUGGLES AGAINST MISERY AND POVERTY … “WE NEED MONEY URGENTLY”’. The Citizens Welfare Service of Australia, an independent charitable organisation devoted to fostering the ideal of ‘self-help’ among the poor, had sought out and sponsored the exhibition’s visit. Similarly, in Sydney, a newspaper article announced that, ‘Appropriately, proceeds of the showing will go to the Family Welfare Bureau’.7 The exhibition was an inclusive event: a photograph on the cover of the Sydney Morning Herald showed a singing poet recording her impressions of a three-metre high photograph of the construction of a dam in India for the Blind Institute’s tape recording library (‘Blind will “see” noted exhibition’).8

The Family of Man’s vision of global humanity is worth noting in the context of the White Australia Policy, then being gradually dismantled. As the historian Anna Haebich notes, the exhibition arrived in a context in which ‘Australia was pushed to reconsider its unifying race-based vision of nationhood – a White Australia built on the twin pillars of Anglo-Celtic racial origins and cultural heritage – and bow to the newly emerged international democratic model of nationhood that advocated human rights and equality for all citizens.9 Among the many glowing local newspaper articles greeting the exhibition, one showed two concentration camp survivors now living in Melbourne pictured below an image in the exhibition of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. But despite its imagined global community, the exhibition was an American product. It was organised by an American museum, funded by the Rockefeller family, and the majority of the photographs included were by US-based professional photojournalists who travelled to all corners of the globe. The US Information Agency funded the exhibition’s ambitious touring schedule to promote America’s new status as a superpower and to spread positive images of US democracy in the context of America’s Cold War cultural diplomacy campaign. In 1959, The Family of Man also toured to Moscow.

As an exhibition experience, The Family of Man was less concerned with individual photographers and their creative visions than conveying a simple message for a mass audience. Indeed, reflecting on the experience in 1978, Australian photographer Le Guay – who was included in the exhibition – bemoaned that ‘The Family of Man indicated a great deal about Edward Steichen but little about individual photographers who were mostly represented by a single print; a practice which today is rightly disappearing’.10 Nevertheless, the exhibition gave a confidence boost to local photographers. David Moore even cashed in on his prominence. He invited Wayne Miller to open his solo exhibition Seven Years a Stranger, which featured eighty-two of his own photographs taken on assignment overseas, at Melbourne’s local Museum of Modern Art (a commercial gallery established by John Reed and Georges Mora) while The Family of Man was showing up the road. The poster for Seven Years a Stranger featured Moore’s image of a couple on the Staten Island Ferry approaching Manhattan, announcing his own position in the world as an international photographer who had returned to Australia. Meanwhile, in Sydney, the director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Hal Missingham, took the unusual step of writing a letter to the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald, declaring the exhibition an ‘undeniably moving experience’, noting the snobbery of ‘most official bodies concerned with so-called “fine arts”’ and encouraging readers to visit:

The Family of Man photographic exhibition, at present showing in the city, is a superb example of one aspect of the visual arts which is perhaps peculiar to our century and which receives only tardy recognition from most official bodies concerned with so-called ‘fine arts’ … This is an artistic experience which no one should miss.11

Missingham was himself an artist and photographer, and only a few years prior had exhibited a similar style of unstaged records of contemporary life at David Jones as part of the 1955 exhibition Six Australian Photographers with Gordon Andrews, Max Dupain, Kerry Dundas, Axel Poignant and David Potts.12 Potts showed some of his abstract colour work produced in London, and the catalogue cover seems to evoke Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings.

The Family of Man had a lasting influence on photographers who saw it in Australia, and on Australian photography more generally. Its philosophy and its magazine-like mode of display was directly embodied by Melbourne amateurs Group M in the 1960s, whose leader Albert Brown was central to the establishment of the photography collection and department at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV). The exhibition cemented a model of humanistic documentary photography that was to dominate 1960s Australian practice, in which photography was understood as a universal language. Even later generations of gritty street photographers acknowledged its influence. For instance, writing about his own work in 1974, the Australian photographer John Williams said: ‘The Family of Man set me off, and I’ve been trying ever since. Trying to become a photographer, and not just someone who take photographs’.13 The Family of Man was not actually the first of MoMA’s photography exhibitions to visit Australia; David Jones in Sydney had exhibited one of MoMA’s travelling ‘multiple’ exhibitions, Creative Photography, in 1947, and its strikingly modern layouts were then reproduced by Eric Keast Burke in the Australasian Photo-Review in 1950.14 However, The Family of Man exhibition consolidated MoMA’s role as the most influential institutional vehicle for trends in Australian photography that was to continue well into the 1970s.15

-

The Biz, 1 April 1959, p. 15. ↩

-

There were minor variations in the touring copies of the exhibition. For instance, the single colour image in the New York exhibition – a large, backlit transparency in a darkened room depicting the explosion of a hydrogen bomb – was changed to black and white. The entire exhibition is now on permanent display at the Château de Clervaux in Luxembourg and listed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. ↩

-

Edward Steichen, ‘Introduction’, The Family of Man exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1955, p. 4. ↩

-

See, for instance, Eric J. Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950s America, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1995. ↩

-

During 1958 various local attempts had been made to bring the exhibition to Melbourne by groups such as the Citizens Welfare Service of Victoria. ↩

-

‘“Family of Man” Photograph Show’, The Age, 16 February 1959, p. 10. ↩

-

‘Family of Man on Show’, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 April 1959, p. 13. ↩

-

‘Blind will “see” noted exhibition’, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 April 1959, p. 1. ↩

-

Anna Haebich, Spinning the Dream: Assimilation in Australia 1950–1970, Fremantle Press, Fremantle, 2008, 24. ↩

-

Laurence Le Guay (ed.), Australian Photography, a Contemporary View, Globe Publishing, Sydney, 1978, p. 5. ↩

-

Hal Missingham, ‘Letters to the Editor – “Family of Man” Exhibition’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 April 1959, p. 2. ↩

-

The fact that Hal Missingham was exhibiting his own photographs ten years into his term as director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales is in itself remarkable. ↩

-

Graham Howe, New Photography Australia, A Selective Survey, Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, 1974, p. 74. ↩

-

Ann Stephen, ‘MoMA’s exports’, in Ann Stephen et al (eds.), Modern Times: The Untold Story of Modernism in Australia, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2008, pp. 195–6. ↩

-

Founded in 1929, MoMA began collecting photography in 1930 and presented their first photography exhibition in 1937 (the major Beaumont Newhall exhibition on the history of photography from 1839 to 1937). MoMA held their first one-person exhibition, by Walker Evans, in 1938, and established their Department of Photography in 1940. ↩